Total star rating: ★★★★★

The works: ★★★★★

The show: ★★★★★

If you have heard about any one work of art in the ambitious and urgent Monuments show in Los Angeles, it is probably the beast of a bronze equestrian sculpture by Kara Walker. Her contribution is so central to the show that she is credited as a co-curator. The work, titled Unmanned Drone (2023), is so ambitious that it occupies its own venue, The Brick, while all other works are displayed at the Geffen branch of the Museum of Contemporary Art (Moca). And it represents one way—certainly the most hands-on—of responding to the hotly politicised removal of Confederate monuments that has in recent years impacted US cities from Baltimore to Montgomery.

Walker took a massive monument of the Southern general Stonewall Jackson charging into battle on horseback and basically butchered it. Drawing on actual butcher diagrams, she made mincemeat of the horse and beheaded Jackson, severing his limbs, to create her own disjointed, Frankenstein creature.

The curators have embraced a more flexible, freewheeling and thought-provoking approach

The original statue, and an even larger monument to the Confederate general Robert E. Lee nearby, had long stood in Charlottesville, Virginia. But fuelled by community outrage, the city council voted to remove them in 2017, triggering a deadly neo-Nazi rally there that summer. A few years and lawsuits later, the statue came down, and the Monuments co-curators—Hamza Walker of the Brick and Bennett Simpson at Moca—offered it to Kara Walker. She opted to turn the patinated bronze and heroic vocabulary of the sculpture against itself, exposing the grotesque underpinnings of Confederate history and present-day Lost Cause ideology, which romanticises the South’s battle as a valiant fight for state rights. The New Yorker magazine’s Julian Lucas rightly called the work “at once an act of carnivalesque retribution and a recognition of the Confederacy’s zombie-like persistence”.

Kara Walker’s Unmanned Drone (2023) Commissioned by The Brick; Courtesy of the artist and Sikkema Malloy Jenkins Photo: Ruben Diaz

The other works that make up the exhibition do not respond nearly as directly to the decommissioned Confederate monuments mixed into the show. This is a good thing. A more predictable show would have invited, say, 15 Black artists working today to each respond to one Confederate statue that has been dethroned and moved to the museum. It would have been too neat and maybe even preachy, positioning all artists as the annotators instead of makers of history. It would have been a show of Black artists revisiting racist monuments—which is exactly how many headlines have blithely summed up this exhibition.

But, in fact, the curators have embraced a more flexible, freewheeling and thought-provoking approach, placing nine Confederate monuments, some of which were already paint-bombed or defaced with graffiti, into searching, expansive and multi-directional dialogues with 19—mainly Black, almost all contemporary—artists.

Perhaps this looser approach was necessary given the difficulty of procuring the hefty monuments from municipalities that have never loaned them out. But it is also in keeping with the originating curator Hamza Walker’s ethos: he is a conversation starter and consciousness raiser, not a logic-constrained builder of arguments.

A few artists successfully take on monumentality itself as a theme, with Hank Willis Thomas upturning a full-scale replica of the General Lee car from the old TV hit The Dukes of Hazzard, and Karon Davis casting her dreadlock-wearing son into an outsized, heroic role; he holds a miniaturised monument by the tail like a Baroque David holding the head of Goliath or, more recently, Charles Ray’s boy holding a frog (2009).

Confronting a monument of American cinema, the Canadian artist Stan Douglas has remade the hugely influential and openly racist 1915 film The Birth of a Nation. Douglas re-envisions the plotline featuring Gus, a freed Black man who basically scares a woman to death and is lynched. Douglas has created four new versions of this story, radically undercutting the original.

Some of the works—including those by Davis and Douglas—were commissioned for the Monuments show. So was a short data-driven and eye-opening video by the nonprofit Monument Lab. Did you know that half of the 50 people most represented in US monuments were enslavers? Also upsetting, if not surprising: the defeated Lee got the royal statuary treatment more often than his vanquisher Ulysses S. Grant, who went on to become US president.

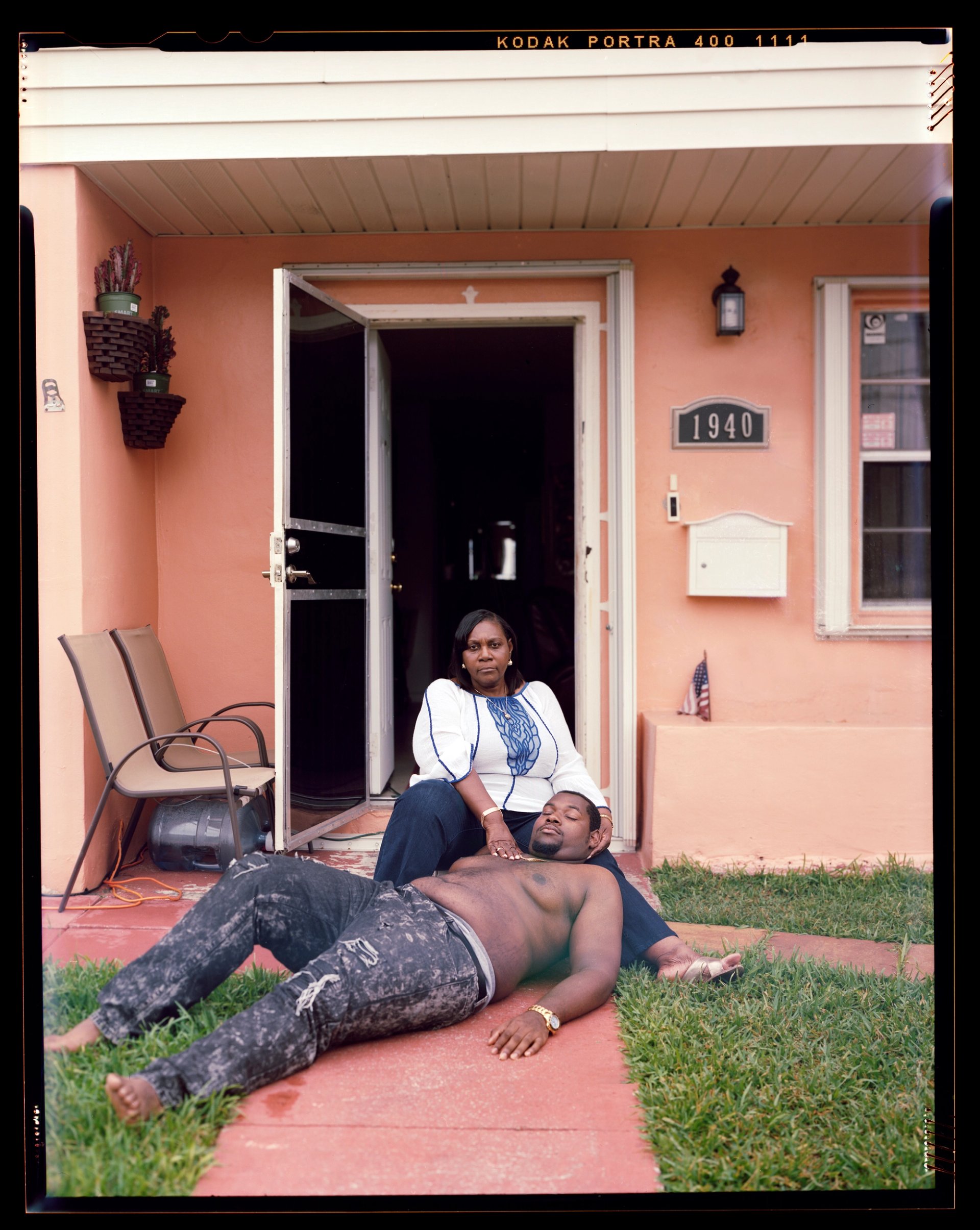

Jon Henry’s Untitled #31; Wynwood, FL (2017) from his Stranger Fruit series Courtesy of the artist

Other artists’ projects in the exhibition were well under way by the time, eight years ago, that a wave of monuments started coming down and the show was conceived. Jon Henry, for instance, began his Stranger Fruit series—photographs of Black mothers cradling their young or grown sons like Christian pietas—in 2014 in response to the epidemic of police killings of Black boys and men. The sons appear lifeless and their mothers blank with grief.

Two years before that, the late artist Nona Faustine began her powerful White Shoes series by posing mostly naked (save the shoes) for photographs at New York sites that had been part of the slave trade. It was a way of using her physicality—brown, female, fleshy—to map a history of slavery in New York that has long been suppressed. Her work does not comment on Confederate monuments as much as displace them. Inserting herself into the supposedly orderly, visibly male, public sphere, she insists on her own, unruly body as a source of power.

One of the break-out stars of the show is the little-known itinerant photographer Hugh Mangum, who lived over a century ago. He worked in the American South in the early 1900s when, as the wall text points out, Civil War monuments proliferated there. His portraits of dignified Black men, women and their children reverberate with a sort of vitality and individuality. (So do their hats.) I especially loved the glass plates from his “penny picture” camera, where portraits of different sitters, a mix of races and genders, appear on one large negative as if an entire, integrated neighbourhood visited Mangum at the same time.

As curators and gallerists know too well, photography has increasingly been plunged into an existential crisis because of the untrammelled flood of digital images and deep (and shallow) artificial intelligence fakes. But Monuments relies heavily on documentary-style photography as a persuasive alternative to government-sanctioned and terribly one-sided versions of American history.

What could possibly be more powerful than the 40 tons of granite and five tons of bronze that make up a heroic Confederate war monument? The image of a strong, naked Black woman standing in white heels on a small wood platform on Wall Street in lower Manhattan, where a slave market once stood. Or the weight of a child’s limp torso draped over his mother’s lap. Or, with a nod to Mangum, a teenage girl’s practised tilt of the head as she flirts with the camera, or some notion of her grown-up self.

Even in today’s oversaturated image culture, photography has not lost its power to share embodied human realities and complexities and a wealth of emotional registers. Here, edging into the vernacular, photographs offer a compelling alternative to the idealising, and falsifying, tendencies of war monuments.

• Monuments, The Geffen Contemporary at Moca and The Brick, Los Angeles, until 3 May

• Curators: Hamza Walker, Bennett Simpson and Kara Walker

• Tickets: $18 (concessions available)

What the other critics said

Julian Lucas writes in The New Yorker that the show “feels even timelier today, amid a moment of ‘anti-woke’ resentment that echoes the Lost Cause”. Lyra Kilston in Apollo calls it “powerful and disturbingly timely”, and wonders if the monuments would seem “more incendiary, or more invisible” outside of liberal California. Christopher Knight in the Los Angeles Times offers this: “MONUMENTS, the all-caps in the title sounding a loud alarm, is the most significant show in an American art museum right now.”