A quintessential genre painter and portraiture artist, Alain Pontecorvo sees the world not through rose-coloured glasses but glasses that are a colour only he knows. We are pleased to be exclusively launching a portfolio of new work by Alain Pontecorvo, accompanied by an essay written by our Artist Relations Lead, Laurel Bouye.

By Laurel Bouye | 11 Jan 2024

On a smoggy November day in Paris, I arrive at a large building in the heart of the Montparnasse district. Taking the elevator to the 13th floor, there is a hand-written note on the door that reads, “Entrez, c’est ouvert.” I recognise the handwriting from packages containing exhibition catalogues that Alain had previously sent to my office. It was a familiar penmanship, perfectly cursive and right-slanting, like something out of a 19th century manuscript.

I walk into his living room-cum-studio. It’s a massive open space flooded with natural light, even on a gloomy day like this. Along the walls are canvases stacked six deep. Inward-facing so as not to be damaged by the sunlight, they’re begging to be unturned and marvelled over; this place is brimming with years and years of art.

Alain, warm and disarming, greets me and invites me to sit in a black armchair. As he begins to show me the portraits he’s worked on, it dawns on me that I’m in the chair. – the chair that has seen so many portrait sitters over the decades. This is the chair that holds those who hold the stories that Alain conveys with his ubiquitous eye, through his adept play with light and frank, unapologetic approach.

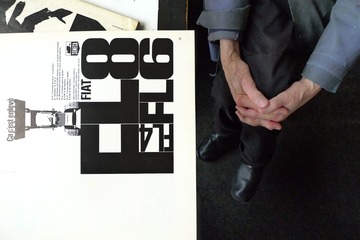

Alain began drawing at the age of three and has yet to stop. He studied in Paris, both before and after being drafted into the French army. He was particularly interested in the field of typography. This led him to work in advertising, an industry in which he would stay and be met with great success for over 15 years. During this time, he worked alongside some of the largest names in the industry and even invented his own font: the Pontecorvo.

These endeavours, however, distracted him from his real love, his life-calling. He knew he was supposed to paint and draw. And so he did.

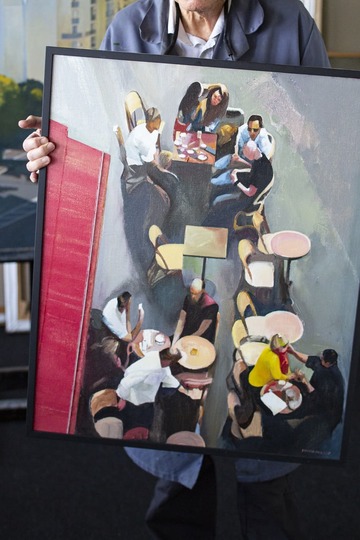

Alain Pontecorvo is the quintessential genre painter and portraiture artist. His subject matter is as diverse as his career has been long. He never leaves home without a sketchbook, of which he has over 600. He works in a capture-the-moment sort of style that is honest, unpretentious and, most of all, candid.

If you were to sit for a portrait with Pontecorvo, he would not necessarily paint you at your best, but at your most human. “For me,” Alain explains, “it’s all about working with light and shapes in space. I do a portrait like I do an apple or a car. You don’t need to know anything about the person’s life. I choose the position that best conveys their attitude, and depending on the light, the structure and the composition, everything else falls into place.”

When Alain begins a portrait, he doesn’t “question the life of the individual. Life will come into the painting through [his] construction and [his] observation.”

A similar approach is taken for Alain’s genre scenes, landscapes and cityscapes. He’s not seeking to evoke some ethereal beauty or glorify a higher power when he paints the rolling plains of the French countryside or a sun-drenched terrace during golden-hour. His intentions are much less haughty; he paints these things because he finds them pleasing. “A well-lit apple on the table,” he says, “makes me happy.”

His work compels us to notice the subtle splendour all around us: the way the sunlight reflects off of a car, the train station’s satisfyingly geometric architecture that perfectly frames the platform, the way a pedestrian’s shadow lags faithfully behind them on their commute home. He finds light and beauty within the quotidian.

Why is it that we can always look at a painting and tell it’s a Pontecorvo? Is it his photographic-like composition? Or his sun-bathed settings that make it hard to distinguish painting from reality? Or perhaps it’s the soft lens through which he allows us to see his surroundings. Through his work, he romanticises the mundane. He sees the world not through rose-coloured glasses but glasses that are a colour only he knows, one he’s conceived. He looks where everyone has looked and can see what no one else has seen.