The acclaimed photographer and artist Anastasia Samoylova (b. 1984) produces images that aim to capture the “emotional complexity of the American landscape today.” This is an overwhelming endeavour, to say the least. She describes herself “as an immigrant who has now spent half her life in the United States.” Born in Moscow in 1984, in what was still the Soviet Union, Samoylova studied environmental design in Russia, using digital photography to record her 3D constructions whilst growing curious about it as a narrative tool. She then moved to Illinois to pursue an MFA at Bradley University, and began to develop an artistic lens-based practice.

“My path into photography has been shaped by movement between places, languages, and ways of seeing,” Samoylova says. “I have always been interested in how images construct our sense of space.” In 2016, the artist settled in Miami Beach, Florida, and consequently learned more about the climate’s critical state. Miami’s glossed image, aggressive urbanising and tourist-driven consumerism is inherently unstable. Ecological and social crises fester beneath the pursuit of the beautified, photogenic and picturesque. For instance, apartments are built with sea views – more beautiful, more expensive – whilst discounting that they are in high-risk flood zones. So many constructions flirt with unexpected collapse.

“I am drawn to the ways beauty, aspiration and vulnerability intersect in the landscape and to how images can reveal the fragile balance between what we desire and what we risk losing,” Samoylova says. These visual investigations have taken different shapes across her practice. The Landscape Sublime series disrupts how we consume ubiquitous nature photographs, from desktop screensavers to luxury billboard ads, which affect our perceptions of nature. Meanwhile, FloodZone, Samoylova’s first monograph, published in 2019 by Steidl and presented at Eastman Museum, specifically explores the looming pall of rising sea levels on south Florida.

Meanwhile, the Floridas series comprises photos from many road trips across the state, documenting pluralities and fault lines via buildings, objects, symbols and more. “I have always been aware of how the built environment reveals the values and pressures of a society,” Samoylova says. Her photos record a community not in disaster, but perpetually anticipating one. This is a landscape that has been built upon and continually exhausted, all whilst steadily losing a fight with the ocean. It treads hyper-utopia and ruination at once.

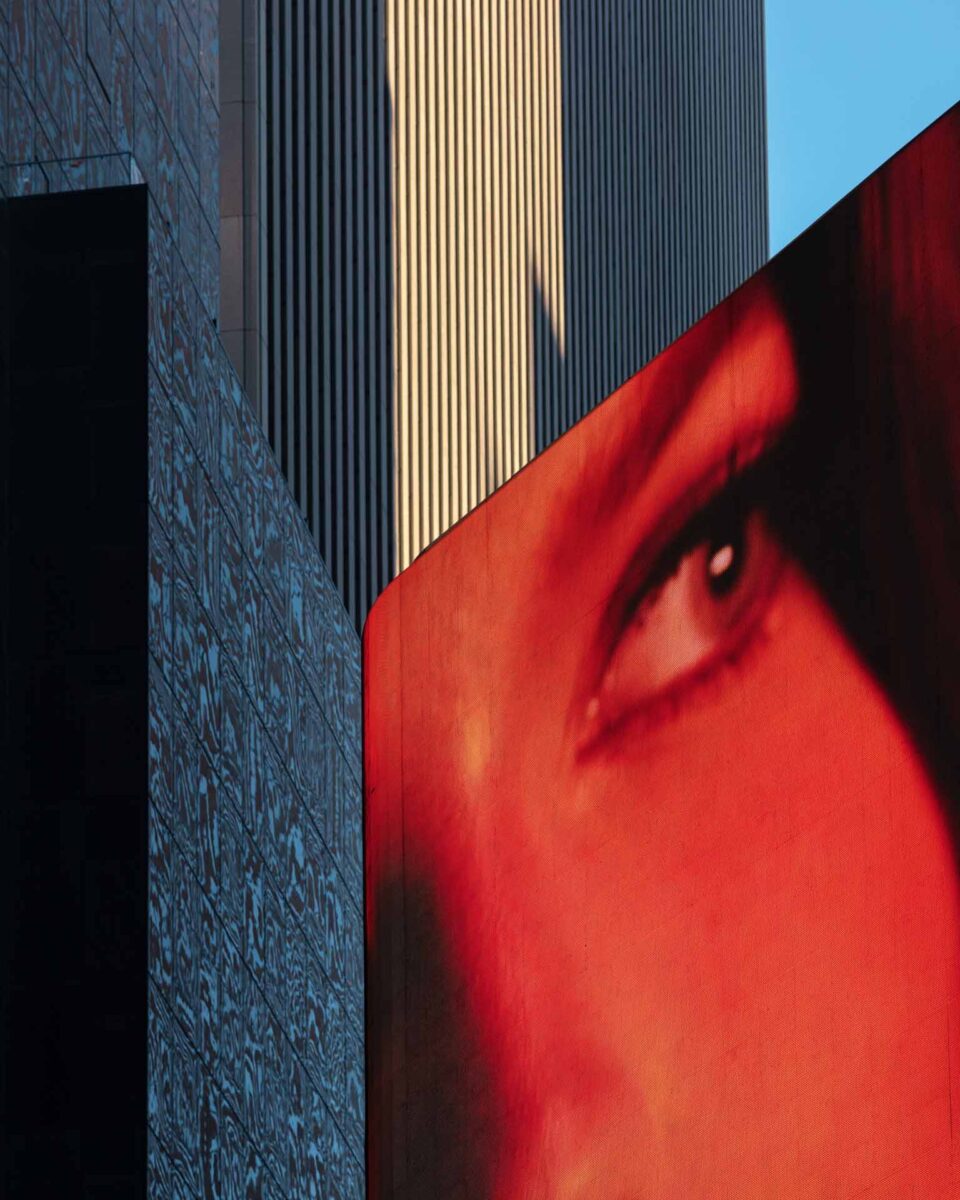

What’s striking about this is that, the more you keep looking, the more you begin noticing that same unnerving sheen in your own environment – and in so many cities across the world. The question: is it all becoming one big metropolis? Samoylova’s Image Cities goes deeper into this, recording how major hubs like New York and London try to assert their distinctiveness, yet succumb to appearing the same due to generic, homogenised advertising and architectural aesthetics. “These projects are connected by a continuous interest in how people inhabit vulnerable landscapes,” the artist says. Shooting on location is thus essential. Samoylova, in fact, views it as a form of field work. “Being physically present in these locations lets me see how the atmosphere of a place shifts, how history leaves its mark, and how people can adapt.”

In her latest project, Atlantic Coast – presented at the Norton Museum of Art and as a monograph published by Aperture – “the themes are similar, but the scale is different.” It is also the first where portraits of people play a significant role. Atlantic Coast comprises colour and black-and-white documentary photographs taken along the historic US Route 1 running from Fort Kent, Maine, to Key West, Florida, inspired by Berenice Abbott’s 1954 project on a road trip along the same route. Both Abbott’s work and Atlantic Coast capture the American nation at a particular historical moment. Samoylova explains how the magnitude of doing such a project required a different tempo. She spent more time in smaller towns and quieter neighbourhoods, meeting and photographing people along the road, and hearing their stories and how intimately tied they are to the land and coast.

As an immigrant and American citizen, with a dual perspective, Samoylova mentions she related to Abbott’s affectionate-critical approach to America. That carries into her images, which are less judges of the nation than they are mirrors. A coat hanger twists into the words “affordable healthcare” against a rose-tinted golden hour sunset. A shadow of a boy or a man is engulfed – or caressed – by a large American flag. Gun Ring, Brooklyn, NY (2024) zooms in on the aged hands of a white woman wearing an American flag scarf, matching bracelets, and a bedazzled gun-shaped ring. There’s a quiet, ordinary violence embedded into “fun fashion.” The viewer has to ask: What is the real weight of the symbols we wear?

Atlantic Coast brings to mind other great photo projects that sought to visually bottle some of the mythmaking scaffolding the story of America. Robert Frank’s The Americans; Stephen Shore’s Uncommon Places; Joel Sternfeld’s wide-ranging work. Samoylova emphasises that, whilst these artists “were all looking at the mythology of America through the open road, [she is] looking at it from the shoreline, a place of arrival and departure, fragility and defense.” It was also important for her to offer a female perspective within a genre that has been shaped largely by men. Part of this, for Samoylova, is imbuing the shoot, and the finished image, with emotional sensitivity. Her pictures do not relish in brutality, dysfunction or despair. They discuss these aspects of their subject, but make their impact without necessarily stoking violence or rupture between the image and its audience.

The pictures in Atlantic Coast are organised by theme, similar to Frank’s The Americans. “The project was never meant to be a literal record of a route. I wanted the sequence to unfold through ideas and atmosphere rather than strict geography. Organising the work in this way allows viewers to feel the shared rhythms and tensions that define the Atlantic Coast. Flags, fences, scaffolding, floodlines, hand-painted signs, and those fragile edges where land meets water … people whose stories were inseparable from their environments.”

Samoylova takes a more fluid approach to the oft-masculine “on the road” project of documenting America. It’s important to note, also, that it is far less safe for women to travel as they please across any country. Like the Caribbean theory of tidalectics, which uses the movement of the ocean to understand history and culture, Samoylova’s visual framework theorises from the coast rather than the road or land, “where the horizon becomes both a mirror and a quiet warning.” In her images, we see the fruits of waiting in stillness, of observing something long enough for it to reveal other narratives. These stories may be of political tension or division; infrastructural collapse or rising water; or simply an uneasy Atmosphere or reluctance to talk about the future – let alone believe in it being better than the present. Objects, symbols and images are, after all, silent repositories. “I was not trying to illustrate these divisions directly. Instead, I was interested in how they seep into the everyday environment, how they shape the mood of a street or the way light falls on a building … small everyday scenes can hold the larger story of a place, the visible and invisible forms of work and memory.”

The current US president’s desire and slogan to “Make America Great Again” calls for a return to a mythical, idealised national past and distracting patriotic fervour, with no clear plan on how the nation as it is now is to overcome its multifarious issues – much of which is caused and exacerbated by deep foundational ideological and structural problems. In Florida itself, water crises alone abound and worsen by the day. According to a report issued by the South Florida Water Management District, some coastal wells now show chloride levels above 10,000 mg/L, making the water essentially undrinkable. Factor in the growing reliance on artificial intelligence, the data centres for which use millions of gallons of freshwater a day in some regions, worsening local shortages and overall negatively impacting the climate crisis.

“Travelling along Route 1 made it clear that the past is not a single story,” Samoylova says. “It is complex and often contradictory. That tension between nostalgia and reality shapes the mood of many places.” There are other contemporary photographers who are telling stories that complicate the image of America and its multiple regions and communities, especially through the lens of the climate crisis. Camille Seaman’s The Big Cloud (2008–2014), for instance, involved the photographer chasing a specific thunderstorm called a supercell across the USA. The series, shortlisted for the Prix Pictet 2025, drew attention to those living in towns affected by extreme weather. Seaman’s artist statement offers a similar human experience to that of Samoylova: “It was important to remember that these people lived here year after year, never knowing if this was the year, the month, or the day when a tornado might come through their town.” Encountering such communities shored up immense empathy within Seaman for the localised impacts of major climate events. The process brought local people’s stories to the surface, countering the tendency to reduce them to nameless, faceless statistics.

Likewise, Spanish photographer Cristina De Middel’s acclaimed series Journey to the Center (2021) focuses on the Central American migration route, starting in Tapachula on the southern border of Mexico and ending in Felicity, a small town in California. This is often painted in the media as a desperate escape route – or a fugitive’s path. De Middel visually rewrites it as a hero’s road, tread with extraordinary courage and strength. To do so, the artist combines documentary photography with constructed images and archival material.

Creative minds like Samoylova, Seaman and De Middel are helping to forge a new path for younger generations of image-makers, especially female artists, who can take up the mantle, or responsibility, of observing, listening, and documenting the many different stories that contribute to US mythmaking. Such work holds up a mirror but also serves as a force to keep ourselves, as humans, accountable to each others’ struggles and stories. As Samoylova puts it: “The future of the coast is uncertain, but not without possibility.” It is vital, amid growing despair, that we advocate for the future of our homelands and communities with this very same spirit.

Atlantic Coast | Norton, West Palm Beach | Until 1 March 2026

Words: Vamika Sinha

Image credits:

1. Anastasia Samoylova, Fireworks, Fort Knox, Prospect, Maine, (2024). Image courtesy of the artist.

© Anastasia Samoylova

2. Anastasia Samoylova, Bar, Miami, Florida, (2025). Image courtesy of the artist.© Anastasia Samoylova

3. Anastasia Samoylova, Drying Jeans, Ft Lauderdale, Florida. (2024). Image courtesy of the artist. © Anastasia Samoylova.

4. Anastasia Samoylova, Red Eye, Times Square, New York, (2021). Image courtesy of the artist. © Anastasia Samoylova.

5. Anastasia Samoylova, Reflection in Black Thunderbird, Palm Beach, Florida, (2024). Image courtesy of the artist. © Anastasia Samoylova

The post Routes Transform appeared first on Aesthetica Magazine.