“The paintings become a record of a battle,” she tells me: a battle between portrayal and distortion. She exercises limited power over the latter, meaning that she can never be quite sure how a painting will turn out until it is finished; “I relinquish control and allow the paint to behave according to its own material tendencies.”

By Phin Jennings | 30 Aug 2023

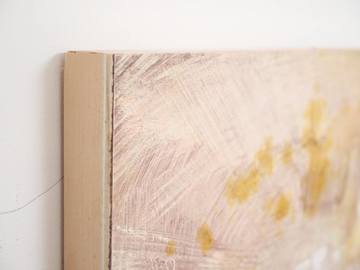

I hadn’t seen one of Fleur Patrick’s paintings in person before I visited her studio this summer. When I did, I found them to be best viewed up close. When you move away from a work, she explained to me “it becomes just an image.” Up close, you become aware of its overwhelming materiality. Of course, there is a pictorial element to what she does – each painting can be said to be of something, normally a faintly rendered, abandoned interior space – but, looking at them more closely, I became interested in those elements of the artwork that do not serve a representational function, where the artist is, in her own words “collaborating with the paint”.

At the centre of Patrick’s practice is a negotiation between image and materials. In each painting, she negotiates between representing her subject and embracing the unpredictability of her medium. Where many painters simply use paint as a tool to portray their subjects, Patrick also allows it to obscure them. “The paintings become a record of a battle,” she tells me: a battle between portrayal and distortion. She exercises limited power over the latter, meaning that she can never be quite sure how a painting will turn out until it is finished; “I relinquish control and allow the paint to behave according to its own material tendencies.”

Again, and yet again, we looked back, for example, contains in its top right corner a relatively uniform and hard-edged grid, reflecting the shape of a large atrium. My eye starts here and is drawn clockwise around the image as this form falters and, eventually, lapses completely. The bottom portion of the painting is a mutiny of pink, blue, lilac and orange. The layers of oil paint, though thin, overpower any intentional structure that might lay beneath them.

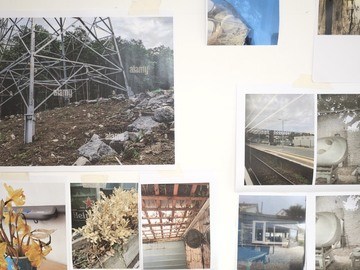

The objects, photographs and artworks on Patrick’s studio walls reflect this battle between calculated figuration and unfettered abstraction. There are photographs of structures like those in her paintings, and rulers and rolls of tape that help her to render them faithfully. There are also small studies on paper that bear no reference to her figurative subjects, instead containing constellations of purely abstract form and colour. These works, which she calls the Remains of the Day series, are the products of experiments that she conducts with the paint left on her palette at the end of each day. These experiments – mixing, pouring, dabbing and scraping paint, pushing it in a certain direction or letting it run free – inform the paintings on panels hanging on the opposite wall of her studio. “You always need to play,” she assures me, “it’s vitally important.”

She starts each painting on panel by tracing an outline using a pencil and ruler. In order for this bottom layer to function as an image, rather than a more comprehensive representation, it is important that she is not too familiar with the space that she is drawing; otherwise, she says, the artwork will become “overly descriptive.”

She then uses Liquin, a medium that increases the transparency of oil paint and allows it to flow more easily across a substrate, to create translucent layers of colour over the top of the drawn structure. She applies and removes paint with a brush, cloth or pipette. She sometimes works on the wall, where it drips down the panel, and sometimes on the table, where it pools in dark spots. The liquin-diluted paint dries quickly, meaning that there is limited time to contend with each layer before it becomes entrenched. Patrick seems comfortable with the fact that “part of the process is understanding that some of them won’t work.” This is, after all, a collaboration, and she can’t expect to get her way every time.

Some of the paintings’ underlying structures are rendered almost invisible by the layers of paint on top. In others, they are easy to see through the haze. Always, they have a nebulous, hazy quality, like half-forgotten memories. They are as much about the process of making them as they are about their subjects; they are about ambiguity and uncertainty. Patrick’s methods don’t lead to a controlled and easily-legible outcome, and that’s the point. “The minute you get comfortable,” she tells me, “I don’t think you’re fully engaging.”