Current and former staff members at Queens College, a part of the City University of New York (Cuny), are voicing concern about the condition of works of art both in the Art Library’s collection and outdoors on campus—including pieces by Anni Albers, Pablo Picasso, Alice Neel and Vito Acconci. They cite damage to works both on public view and in storage, as well as missing objects and insufficient support to properly catalogue and protect the art. Staff reports, bolstered by recorded instances of internal and external complaints over the past several decades, allege decades of systemic neglect of the works in the college’s art collection.

“Chronic lack of funding is the root of all neglect,” former Queens College substitute art librarian Amanda Perez tells The Art Newspaper. (Perez resigned in March 2024, after only four months on the job, citing the conditions of the library and collection. She was formerly a picture researcher for The Art Newspaper.) Budget cuts are affecting the college institution-wide, as seen with the recent decision not to reappoint over two dozen professors, announced just before the spring semester began. Queens College was one of eight schools whose budgets Cuny reduced after New York City mayor Eric Adams cut the publicly funded university system’s financing by $23m last November as part of a revised municipal budget.

Nevertheless, some of the earliest reports of issues with the art on campus at Queens College have been lying in plain sight for years, well before recent funding issues could be blamed. For example, in a 1999 letter to the editor of The New York Times, a Queens resident voiced concern for Acconci’s 1995 commission More Balls for Klapper Hall (or Untitled) at Queens College. The site-specific work consists of concrete orbs with voids cut into them, so that they can be used as furniture. Inside the cuts are frosted acrylic panels and lights. The letter raised alarms that the work had been vandalised with graffiti inside the orbs and that some were broken, damage still visible 25 years later.

One of Vito Acconci’s Balls for Klapper Hall, slowly disintegrating and covered in years-old graffiti Photo: Amanda Perez

Gregory Sholette, a professor of sculpture and social practice at Queens College, has witnessed damage to this and other outdoor sculptures. “By the time I arrived in 2007, the lights [in Acconci’s work] had stopped functioning, parts of the spheres were damaged, some even were missing and two half-spheres had been composited together,” he tells The Art Newspaper.

A representative of Queens College confirmed this in a statement, saying that two half-spheres “were deemed unsafe for use as a result of having become detached from rusted ground anchor rods. Staff balanced them together in one sphere and then placed the structure on a wooden base for safekeeping so that they might remain with the rest of the installation until such a time when they could be restored.”

But Acconci’s work has faced additional damage more recently. “About a year or so ago, someone in a vehicle doing construction knocked two other half-spheres down, and they lay there being damaged by weather for about a week,” says Sholette. Faculty and staff brought the damage to Queens College president Frank H. Wu’s attention and, Sholette says, “pointed out that since the university is now promoting a new school of art, it would want to address this rather important artwork in its care—as well as others, of course”. (The new art school opened in 2022.)

Sholette adds that Wu commissioned a professional conservation report to repair Acconci’s work and bring it back to its original illuminated status. “Some repairs were made, although the full-scale restoration is now stalled, perhaps due to a lack of funding,” Sholette says.

Close-ups of damage to two of Vito Acconci’s Balls for Klapper Hall Photo: Amanda Perez

Queens College confirms that only the first of the two-part conservation plan has been completed: “The second—long-term—phase involves the creation of a comprehensive research, conservation, maintenance and archival plan with the same conservator for all of the Acconci sculptures. The college is currently exploring efforts to implement this plan, as well as one for the conservation and maintenance of all campus art structures.”

But given the financial situation at the college, the future of Acconci’s work—and that of so many other pieces on campus—remains uncertain. “Queens College was burdened with a $4m cut this year,” Sholette says, “adding to the decades of austerity imposed on colleges by the state and city.”

From optimistic beginnings to relative neglect

Queens College’s Art Library was originally founded as a book collection in 1937. It began acquiring art in 1948 after the donation of several hundred prints, dating from the early Renaissance to contemporary works, from the personal collection of Audrey McMahon, co-founder of the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project. These works became part of the Queens College Art Collection, which was formed in 1957 as a teaching collection and continued to grow through additional donations.

Concerns about the collection have been documented throughout the years in the library’s annual reports, revealing the long-term nature of issues that continue to this day. The 1963-64 report cautions that “storage facilities do not permit the acquisition of additional paintings and anything besides small objects”. The 1970-71 report states that “seven framed prints from the collection that hung in the Reserve Reading Room for several years were stolen … Nothing was ever discovered about the theft, which included lithograph posters by Picasso and Matisse (one each) and a series of 5 silkscreen prints by Rupert [sic] Geiger.”

By the mid-1970s, “the growth of the collection eventually led to problems of storage and accessibility”, the librarian Suzanna Simor said during a 2005 Art Libraries Society of North America (ARLIS) conference. Simor, who joined Queens College in 1977 and oversaw the library until she retired in December 2019, added that “the loose cooperation of art-history and library faculty in its administration and management, coupled with insufficient manpower and minimal support from the college’s administration, eventually amounted to relative neglect”.

A book installation by Matt Greco and Chris Esposito sits precariously under a leaky ceiling in Queens College’s Art Library Photo: Amanda Perez

These issues, along with concerns that the works on view could easily be lost or stolen, resulted in the dissolution of the Queens College Art Collection in 1980 and the creation of the campus’s Godwin-Ternbach Museum in 1981. Part of the collection was transferred to the museum, “and they have since provided care and maintenance for much of the artwork at Queens College”, says Perez, the former substitute art librarian. “Unfortunately, not all the artwork on campus made it to the museum’s collection.”

Some works remained in the Art Library (now called the Queens College Benjamin S. Rosenthal Library Art Collection) along with books, periodicals, papers and ephemera. Staff allege that the art that did not enter the museum has been subjected to mismanagement and damage. Perez also saw significant security concerns, including works of art not fastened to the wall that could easily be stolen.

“The library is in the process of re-inventorying its artwork as well as reinstalling some pieces more securely,” a Queens College spokesperson says of the current situation. “Efforts to remedy conditions in which stored artwork may be at risk are being explored.”

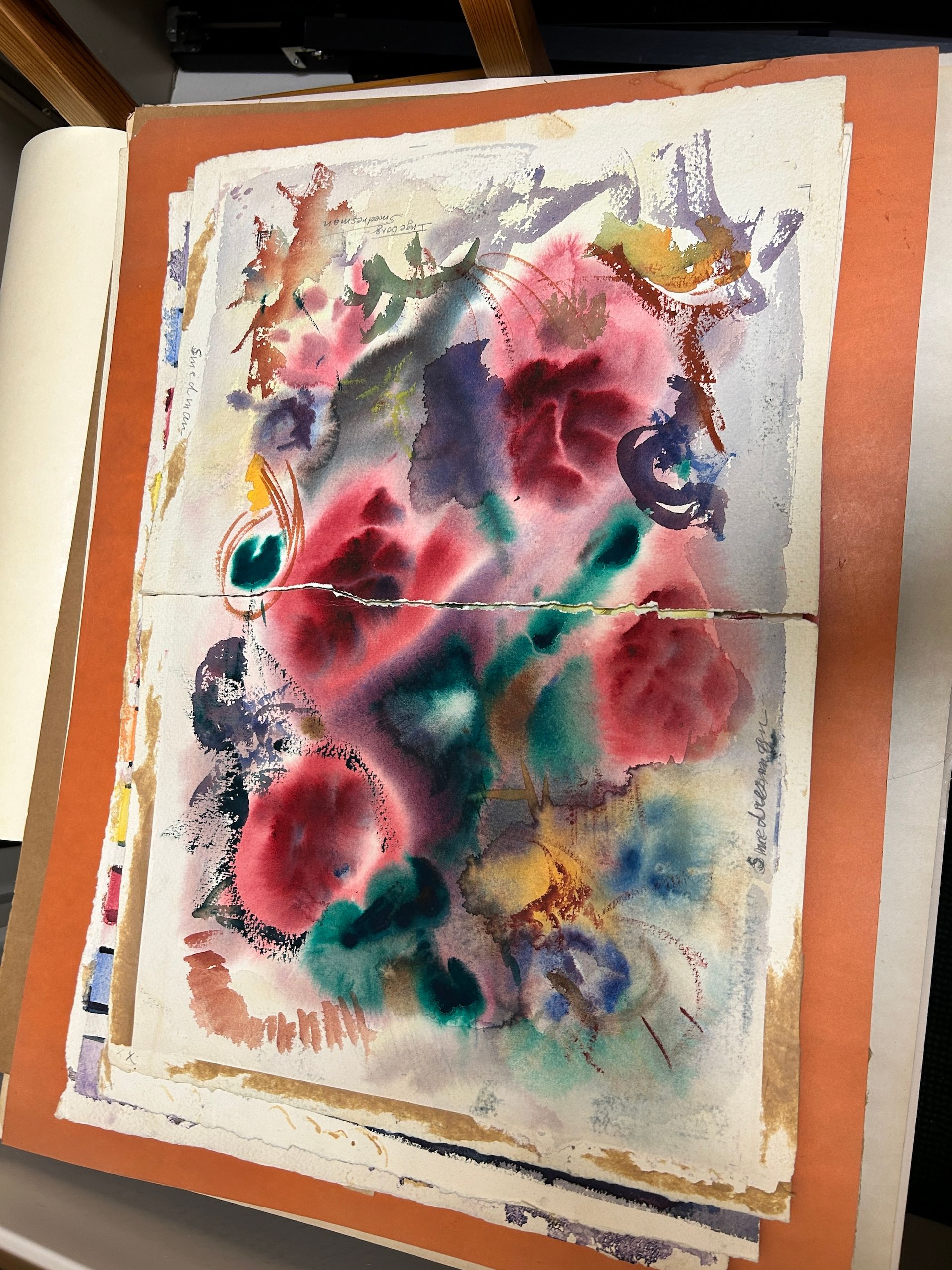

A watercolour by Ingeborg Freundlich Smedresman that has split in half Photo: Amanda Perez

According to Perez, staff has had difficulty managing the collection ever since Simor’s retirement, as the college has not hired an art librarian and instead relies exclusively on substitutes. The Queens College spokesperson cites pandemic closures and budget limitations for this gap in hiring, adding that “the library is currently exploring the hiring of a part-time visual and performing arts librarian dependent upon budget availability”.

But the biggest issue, according to Perez, is the need for a campus-wide records management system to catalogue and maintain the works of art. “No one I’ve spoken to was able to track down a complete inventory,” she says. (Queens College did not address the claim that there is no such system currently in place.)

The need for an overseer

In photographs reviewed by The Art Newspaper, Perez has documented missing or incorrect wall labels (heightening the risk of theft) and improper storage and installation—including works displayed in areas under HVAC systems or prone to leaks. For example, John Ferren’s abstract painting Double Star (1969) hangs under an HVAC vent in the Science Building, and an installation of books by Matt Greco and Chris Esposito is located under a leaky ceiling in the Art Library.

Perez’s photographs document additional damage. “Donated artworks were leaning unwrapped back to back, with the hanging wires scraping and damaging the front canvases,” she says. “Donated watercolours were stacked on top of each other, and adhesive was stuck to the artwork.” These include a watercolour by Ingeborg Freundlich Smedresman that has split in half, as well as damage to paintings by Theresa Zezzos Fulton, a Queens College professor who taught in the art department in the 1970s and 80s.

“All of [Fulton’s] works have either graffiti, cracks, dents or damage from decades of sun exposure,” Perez says. “One of Fulton’s paintings was severely damaged with what looks like a backwards swastika scribbled at the centre of the artwork and significant cracks that indicate the force of impact on the front of the canvas.”

These and other damaged works are clearly visible across campus. Jong-Heung Kim’s Jangseung (2010), an outdoor installation of four vertical carved wooden poles, is mouldy and decaying. One pole appears to have broken and is currently in a plastic bucket and tied to a nearby tree to keep it vertical. An old website featuring several outdoor works at Queens College shows what the work previously looked like. While the images are undated, the social-media links range from 8 to 13 years ago. (Information on some of these links indicate the website was originally created by students at Queens College.)

Jong-Heung Kim’s Jangseung (2010) is mouldy and decaying; one of its poles appears to have broken and is currently in a plastic bucket and tied to a nearby tree to keep it vertical Photo: Amanda Perez

Other sculptures featured on the “Public Art at Queens College” website, such as Thomas J. Doyle’s Cripple Creek (1987), are no longer installed and appear to be missing. According to Perez, staff are concerned that Doyle’s work was possibly discarded. The location and condition of Frank Smullin’s steel sculpture Utica Overland (1980) are also unknown. An undated photo on the website shows it rusted and dismantled, having been removed from its plinth. This sculpture may have been discarded as well. (Queens College did not address questions regarding the location of these two works or whether they had been thrown out.)

Perez says that the question of who is in charge of maintaining these works remains unanswered. She was told that all of the art on campus is owned by the Queens College Foundation, and that the outdoor sculptures—which are not part of the Art Library—were either acquired through the Dormitory Authority of the State of New York or donated. According to Perez, Queens College continues to accept donations of art through the Queens College Foundation. These works enter the collection of the Godwin-Ternbach Museum, which “has proper record keeping, and accession records”, Perez says. However, the care of the art collection elsewhere on campus remains a problem.

“The ongoing issue concerns the need for an overseer,” she says. “An art overseer connected to the museum with stable funding and support can develop best practices for record-keeping and maintenance of campus artwork.”

The Queens College spokesperson says: “Library Art Collection staff and the chief librarian work together to oversee the art in the library collection. Several departments across campus work together collaboratively to respond to inquiries and address issues pertaining to public art works.”

Perez, like Sholette and other staff, has repeatedly raised her concerns about the campus’s art collection with Queens College’s leaders. “They were already aware of the conditions,” she says. “Many departments and art professionals have raised these ongoing issues for decades, and progress seems to stall, and plans change constantly. Art is not the priority; I just hear empty promises.”