For a good part of the past millennium, Paris was, simply and indisputably, the artistic capital of the Western world. Whether it was Gothic cathedrals or 18th-century equestrian statues, Barbizon landscapes or Cubist still lifes, Paris set the tone and then exported its standards, while beckoning artists, patrons, collectors and onlookers to meet up in its medieval alleyways and newfangled boulevards.

The fall of France in 1940 and the triumph of New York in the 1950s and 60s meant that the French capital was destined to become more of a custodian than a trendsetter in the visual arts. But even then, the city broke new institutional ground with a number of banner museum projects.

In the 1970s, the inside-out-looking Centre Pompidou, housing the city’s leading collection of Modern art, proved that museum architecture could create its own sense of occasion. In the 1980s, the Musée d’Orsay, a radically reimagined Left Bank train station, conjured up the crucial decades between 1848 and 1914 by casting a wide net, co-mingling benchmarks of proto-Modernism with forgotten relics of academic painting. And in the 1990s, the Musée du Louvre finished taking over nearly all of its palace premises, becoming a one-stop agglomeration of the history of human expression.

These three museums, contained within a few miles along the Seine, remain the starting points and touchstones for art lovers heading to the City of Light. New additions include Frank Gehry’s Louis Vuitton Foundation, hosting temporary shows to rival anywhere in Europe, and a revived commercial gallery scene that means Paris can once again compete with London and Berlin for the contemporary-art crowd.

Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa (first quarter of the 16th century), Musée du Louvre, rue de Rivoli

Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa at the Musée du Louvre

Image: © aylerein

Leonardo spent his final years in France, but it was not until after he died in 1519 that this mysterious portrait of an Italian noblewoman was acquired by his patron, the French king Francis I. Now the city’s—and, arguably, the world’s—most famous painting, it was for centuries merely one of many masterpieces in the French royal collections. Stashed in the Palace of Versailles by Louis XIV, and then landing in the Louvre after the French Revolution, it was catapulted into the stratosphere on the eve of the First World War following a headline-grabbing theft by a disgruntled museum handyman. But permanent iconic status belies its symbolic importance: the painting’s Italian origins and French pedigree make it a potent reminder of the great transfer of artistic prestige that saw France dislodge Italy as Europe’s creative superpower.

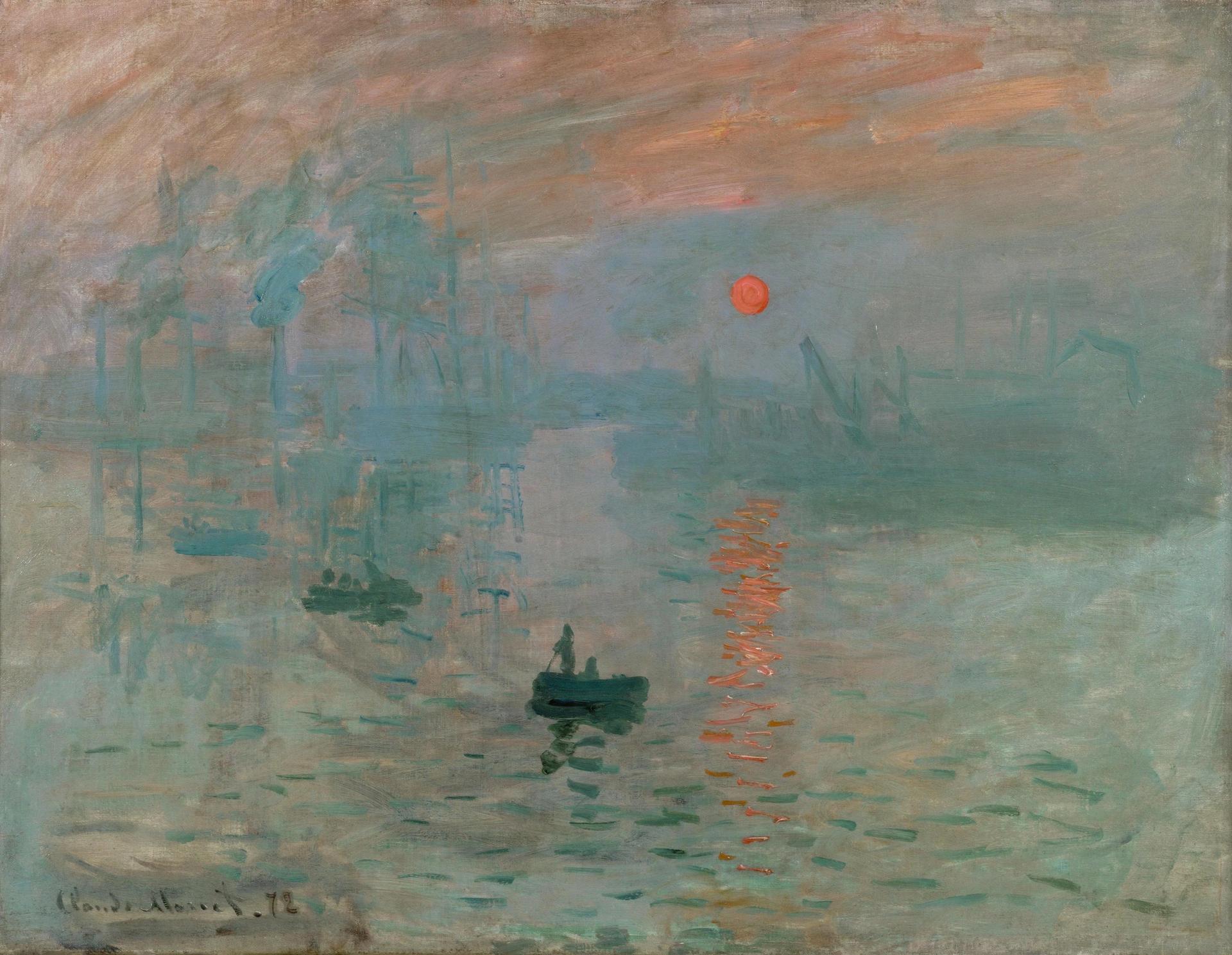

Claude Monet’s Impression, Sunrise (1872), Musée Marmottan Monet, rue Louis Boilly

Claude Monet, Impression Sunrise (1872) © Musée Marmottan

Monet’s hazy, incandescent view of the port of Le Havre gave Impressionism its name in 1874, when the painting was a prime attraction in the Paris exhibition that helped launch the movement. Part of a legacy donated by Monet’s son to an out-of-the-way 16th Arrondissement museum—now in possession of the world’s largest cache of the artist’s works—it is a fitting emblem of an era that began Paris’s great rebranding, converting the bulwark of academic painting and Orientalist frippery into a hothouse of the avant-garde.

The Winged Victory of Samothrace, (first quarter of the second century BC) Musée du Louvre, rue de Rivoli

Winged Victory of Samothrace at the Louvre Image: © Alexandra Lande

Perched on a ship-like plinth in a grand Louvre stairwell, this Hellenistic sculpture depicting the Greek goddess Nike was discovered in fragments on an Aegean island in the 1860s. She was put back together and eventually given pride of place by Louvre curators, who devised an evocative installation, nearly 20-feet high, that manages to make the sculpture’s missing head and arms seem like unwanted baggage. Looming but graceful, classical but surreal, she is typically the first major artwork that most visitors encounter at the Louvre.

Pablo Picasso’s Self-portrait (1901), Musée national Picasso-Paris, rue de Thorigny

Visitors take in Pablo Picasso’s Self-portrait (1901) at the Musée national Picasso-Paris © Associated Press / Alamy Stock Photo

Picasso was only 20 when he finished this talismanic image from his Blue Period, ushered in that year by the Paris suicide of his friend, the Catalan painter and poet Carles Casagemas. Sporting a ragged beard, orange lips and bulky overcoat, this Picasso looks older, wiser, and much bigger than in real life—a massive, world-weary bohemian, beating back yet another winter. Firmly rooted in the post-Impressionist avant-garde (we can see the influence of both Gauguin and Van Gogh), the painting points ahead to Picasso’s transformation a matter of years later from a waif-like Spaniard into the Paris Colossus of Modern art.

The Lady and the Unicorn (around 1500), Musée de Cluny, rue du Sommerard

This ornate Flemish tapestry series was uncovered in a French château in the 1840s. Presenting six allegories related to the senses, the tapestries soon fired up the imagination of Romantic-era France, which was besotted by the Middle Ages at a time when Paris itself had set about becoming Europe’s most modern city. Near the end of the 19th century, the series was taken over by the Musée de Cluny, a 5th-Arrondissement celebration of the Middle Ages and a product, in its own way, of 1840s medieval mania.

André Breton’s atelier wall (1922-66), Centre Pompidou, Place Georges-Pompidou

André Breton’s atelier wall Photo: Jean-Pierre Dalbéra

In the fractious avant-garde circles of interwar Paris, prankish, cryptic Surrealism was regarded as the swan song of figurative art, eating up the past while thumbing its nose at the future. The impresario of the movement, which was literary as well as visual, was André Breton (1896-1966), the poet, critic and amateur ethnographer. The author of 1924’s Surrealist Manifesto, which argued against the use of reason in creating art of all kinds, Breton spent decades filling up his 9th-Arrondissement flat with a cache of disparate objects, including Dada paintings, Eskimo masks, Mexican whistles, and random pebbles. Recreated and preserved in the Pompidou, this Modernist cabinet of curiosities is a reminder that Surrealism was not only an artistic movement but a defiant way of life.

Jean-Antoine Watteau’s Pilgrimage to the Island of Isle of Cythera (1717), Musée du Louvre, rue de Rivoli

Jean-Antoine Watteau, Pilgrimage to the island of Kythera (1717) Photo: Lluís Ribes Mateu /Museu del Louvre, París

Caught between the grandeur of Louis XIV’s Grand Siècle and the earthquake of the French Revolution, France in the 18th century was marked by superficial refinement and lurking melancholy. The fête galante, a painting genre invented and perfected by Watteau, managed to depict the former, while hinting at the latter. The best-known example on view in Paris, his Cythera, shows a jaunt to the legendary birthplace of Venus. It is a beguiling cliffhanger. Have the elegant party-makers just arrived on the island of love, or are they just about to leave it? Is the party at its peak or is it already over?

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Napoleon on the Throne (1806), Musée de l’Armée, Hôtel des Invalides, rue de Grenelle

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Napoleon I on his Imperial Throne (1806) © Musée de l’Armée

Ingres was the Neoclassical artist ne plus ultra, holding down the fort, though the mid-19th century, against generations of Romantic upstarts. Yet he was also its outlier, undermining the movement’s reliance on the stiff and unnatural with a counter-oeuvre of realistic portraits that plumbed Parisian society’s psychological depths. An early work, this hyper-Imperial, entirely static portrait was meant to be monumental in the Neoclassical manner, but another tone is lurking. In Bonaparte’s pudgy, pouty face, nearly swallowed up by ludicrous trappings, we sense something perilously close to mockery. Regarded, even its own time, as a failed piece of propaganda, it may also be one of Ingres’ earliest x-rays.

Edouard Manet’s Le déjeuner sur l’herbe (1863), Musée d’Orsay, Esplanade Valéry Giscard d’Estaing

Edouard Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1862-63) Photo: Solarisys

Second-Empire Paris loved a good frisson, but it got more than it bargained for with Manet’s frank, bucolic, genre-bending masterpiece. A star attraction of 1863’s Salon des Refusés, which displayed works rejected by the Paris Salon’s tradition-minded jury, the painting was actually rooted in tradition (in Titian and Raphael, to be precise). But its uncanny combining of nudity with contemporary dress, while thumbing its nose at painterly pedagogy, was downright shocking. And it still is. Holding court on the top floor of the Musée d’Orsay, surrounded by many of the best-known works of the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, it is the stand-out.

Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa (1818), Musée du Louvre, rue de Rivoli

Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa (1818) © 2010 GrandPalaisRmn (musée du Louvre) / Martine Beck-Coppola

The road to Modernism in the visual arts begins with Géricault. His enormous depiction of an 1816 shipwreck retained certain elements of history painting, but, as a contemporary scene of deprivation and death, it was a world away from the idealism that had come to mark centuries of Western painting. The artist—whose subsequent portraits of the mentally ill seem decades ahead of their time—was still in his 20s when he completed this 25-footer. Its dynamism and drama went on to inspire generations of later artists, including Eugène Delacroix and Édouard Manet, and our own era’s Martin Kippenberger and Paul McCarthy.