Two hundred years after his death, the scandal-ridden, best-selling celebrity poet Gordon Byron Gordon, 6th Lord Byron, the most talked about literary figure of his generation, retains at least three lasting claims on the attention of art history: as a writer who inspired artists, as a portraitist’s subject and as a champion of Europe’s built heritage.

Byron, rated the “first poet” of his age for best-selling verse narratives such as Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage (1812-18) and Don Juan (1819-24), commanded global recognition at the time of his death, when he was living in self-exile from Britain. Great international honour was similarly accorded to him at the centenary of his death in 1924, when the ceremonies at and around Missolonghi—where he had died of fever and overenthusiastic blood-letting by inexperienced doctors on 19 April 1824 after joining the Greek war of independence from the Ottoman Empire—served in part as a delayed centenary celebration of the beginning of the Greek uprising in March 1821. (Greece had been embroiled in 1921 in its 1919-22 war with Turkey.)

Numerous Byron events and exhibitions are planned this year, especially in Greece, Italy and Britain. There has been a memorial service at Westminster Abbey with readings from Byron scholars and family members, a Byronic All-Dayer at the British Library, in London, and year-long events are planned at the Philhellenic Museum in Missolonghi, the Benaki museum in Athens, the Keats-Shelley Museum in Rome, and at Newstead Abbey, the Byron ancestral home in Nottinghamshire. The podcast The Rest is History, presented by the historians Tom Holland and Dominic Sandbrook, has required four engrossing episodes to encompass the full anecdotal scope of the “darkly intriguing” Byron, and of Byromania past and present.

However, with nothing quite to match the scale of Byron: an exhibition to commemorate the 150th anniversary of his death in the Greek War of Liberation, 19 April 1824 at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London in 1974, art museum celebrations in Britain, the country of Byron’s birth, feel more muted than those of a half-century ago. (The National Portrait Gallery, in London, a long-standing locus of Byron scholarship, held a landmark exhibition, Mad, bad and dangerous: the cult of Lord Byron, curated by the poet’s biographer Fiona MacCarthy, in 2002-03.)

Celebrity champion of built heritage

Many of Byron’s cultural concerns speak strongly to the present day. He played the part of the first global celebrity—as writer, traveller, society enfant terrible; the “mad, bad and dangerous to know” libertine forced after the breakdown of his marriage into eight years of self-exile (when he was more furiously productive than ever)—before ringing down a most Romantic curtain of fame by dying young, at 36, while fighting for a cause of national political self-determination that was popular across Europe.

There is a 21st-century topicality in Byron’s poetic diatribes against Lord Elgin for removing the Parthenon marbles, written after Byron had spent the winter of 1810-11 in Athens, witnessing the gaps created in the frieze of the Temple of Athena by Elgin’s agents in the preceding decade. In the year of the 60th Venice Biennale—and the undeniable encroachment of global warming and sea level rises on the built fabric of that city—there is a haunting premonition in Byron’s 1818 “Ode to Venice”, his home in exile from 1816 to 1819: “Oh Venice! Venice! when thy marble walls / Are level with the waters, there shall be / A cry of nations o’er thy sunken halls, / A loud lament along the sweeping sea!”

“Oh Venice! Venice!” JMW Turner, Venice, the Bridge of Sighs (1840), Tate Britain. The painting was the catalogue cover image for the Tate exhibition Turner and Byron (1992). Turner exhibited the picture in 1840 with lines adapted from Byron’s Childe Harold: “I stood in Venice, on the Bridge of Sighs, A palace and a prison on each hand” Photograph: The Art Newspaper

The artist’s inspiration

Like that of his friend and fellow Romantic author Walter Scott, Byron’s work inspired a huge output of plays, operas, symphonies and history paintings in the mid-19th century: the composers of the first rank include Robert Schumann, Giuseppe Verdi, Hector Berlioz and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky; the artists Joseph Mallord William Turner, Eugène Delacroix and Théodore Géricault. The Tate Gallery in London’s Turner and Byron (1992), curated by David Blayney Brown, positioned Turner as both illustrator of Byron’s work—starting with a commission for The Acropolis, Athens, 1822, inscribed by Turner with a line from Byron’s The Giaour (1814), “Tis Greece, but living Greece no more”—and creator of paintings of Byronic landscapes, from the battlefield of Waterloo to the Rhine Valley, Venice and Rome. Turner’s Byronic canvases include the sublimely Claudean Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage—Italy (Tate Britain, 1832) and another commanding large oil, The Bright Stone of Honour (Ehrenbreitstein) and the Tomb of Marceau, from Byron’s Childe Harold (1835). John Ruskin, writing of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage—Italy, said that “the loveliest result of [Turner’s] art, in the central period of it, was an effort to express on a single canvas the meaning of that poem”.

“The loveliest result”: JMW Turner, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage—Italy (1832), Tate Britain. Turner showed the painting with a line from Byron’s poem of the same name: “and now, fair Italy! / Thou art the garden of the world” Photograph: The Art Newspaper

The portraitist’s subject

Byron was the one of the most recognisable, and talked of, figures of his time, when a cult of Byronism grew out of his personal literary, Romantic stance; and when images of the poet were circulated as engravings, either as individual impressions or as frontispieces to editions of his best-selling narrative verse. He cultivated a measured physical and sartorial pose—with carefully coiffed curls, a self-conscious theatricality of dress, a mix of the Near Eastern and British Elizabethan, with menageries of exotic animals an occasional accessory, while seeking to maintain an “interesting”, unhappy “troubled poet” visage. Members of his circle—in particular his publisher John Murray and his friend from Cambridge student days John Cam Hobhouse—were responsible for commissioning some of the best-known portraits of the poet.

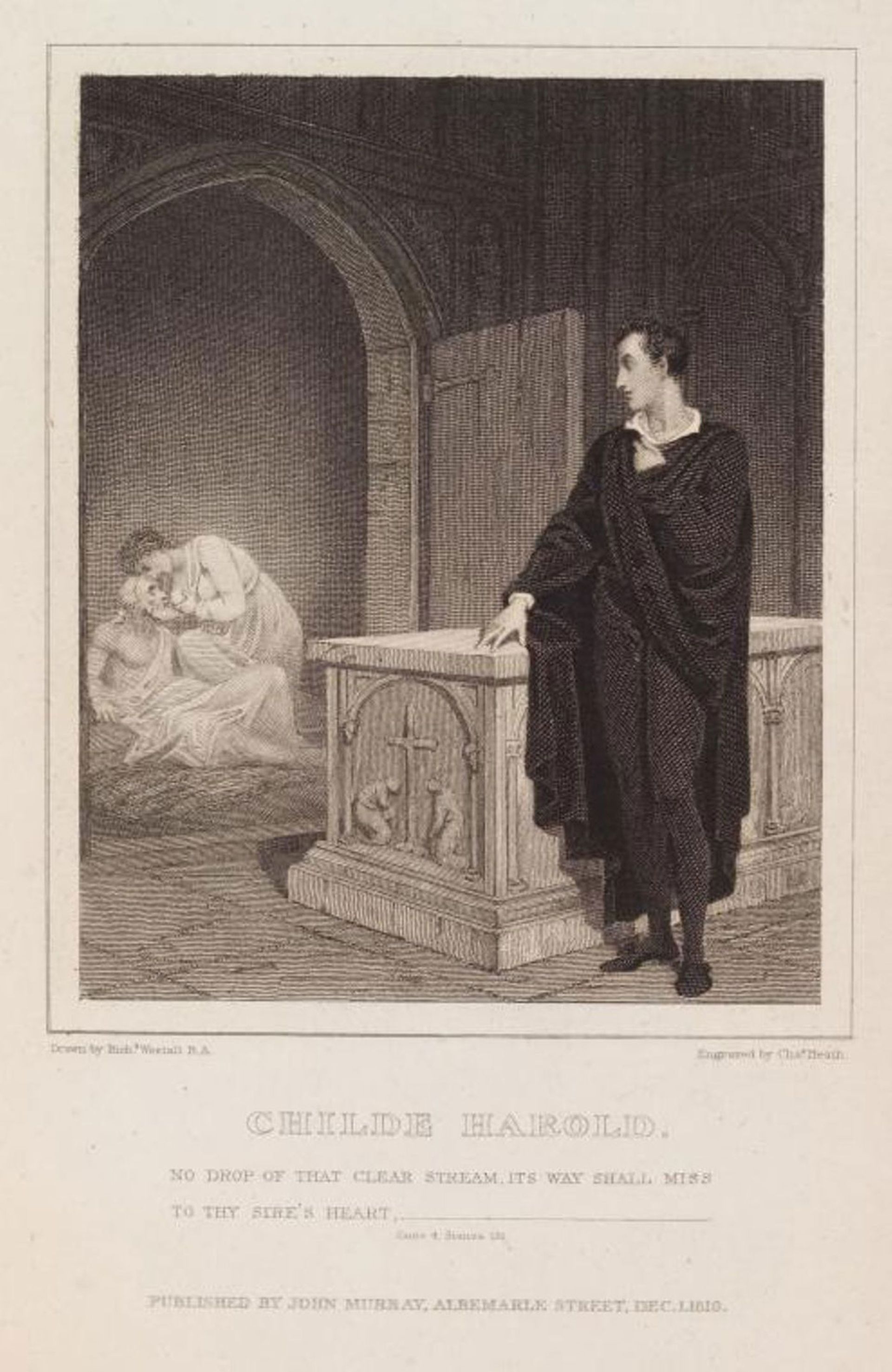

Byron’s reputation as a high-society rake, as much as his political and poetic stance, caused his portrait image to become confused with that of his characters, especially the titular heroes of his best-known multi-part verse narratives—the worldweary grand tour milord of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage and the cynical, promiscuous, but passive adventurer Don Juan—each of them written and published in instalments and enriched with engraved illustrations.

Elided iconography: Charles Heath’s engraving of a Richard Westall illustration shows a most Byronic title character in an 1819 edition of Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage Public domain via New York Public Library

That confusion was made concrete when the same artists both illustrated Byron’s work and made portraits of him. The British painter Richard Westall, creator of a celebrated 1813 portrait of Byron now in the National Portrait Gallery, London, was asked at the same time to make illustrations for editions of Byron’s works. The Westall portrait was reproduced as an engraving almost as soon as the paint was dry, and one of Westall’s contemporaneous illustrations for Childe Harold shows a clearly Byronic title character, with head, attitude, Elizabethan collar and cloak recognisable from the portrait, as indeed from a much-reproduced 1813-14 portrait by Thomas Phillips of the poet sporting a blue cloak.

In a sympathetic review of the third canto of Childe Harold, published in March 1817, a year after the beginning of Byron’s exile, Walter Scott examined the question that had occupied Byron’s readers for the previous five years. “To what then are we to ascribe the singular peculiarity which induced an author of such talent and so well skilled in tracing the dark impressions which guilt and remorse leave on the human character so frequently to affix features peculiar to himself to the robbers and corsairs which he sketched with a pencil as forcible as that of Salvator [Rosa, Scott’s favourite painter].”

Scott does not pretend to have the answer though he ruminates on the Hamlet model where a “radical & constitutional melancholy” is fuelled by “the stings of conscience con[ten]ding with the stubborn energy of pride”. He also considers that all is a disguise “assumed capriciously … at a masquerade” and that this has been maintained to the point that Bryon has assumed “the very semblance and favour of the character he described like an actor who presents on the stage at once his own person and the tragic character with which for the time he is invested”.

The playacting came to an end in Greece in 1824 when Byron—who had admittedly made sure to go stylishly equipped with rakish Classical Greek helmets of the period of the Trojan Wars—assumed a final, and to Byron a fated, role. So that the raft of portraits—paintings, engravings and sculptures—created to promote the writings of the “first poet” of his generation, came to serve as a pantheon for a man who died while still young, the “first poet” of his generation, but also a beguiling traveller, philosopher, and champion of cultural and political independence.