Portraiture has always carried an enduring authority, shaping how individuals are remembered and how communities understand themselves. To look at a face is to encounter a convergence of history, politics and desire, where visibility becomes a form of power. In a visual culture dominated by speed and repetition, the considered portrait still insists on slowness, presence and attention. It proposes recognition as an ethical act rather than a passive exchange. At its most potent, portraiture asks who is seen, who is excluded and who decides the terms of that visibility. These questions sit at the heart of Catherine Opie’s work.

Catherine Opie is widely recognised as one of the most influential photographers of her generation, an artist whose career has redefined the social and political potential of the medium. Working across photography, film, collage and ceramics, she has spent more than three decades examining how individuals locate themselves within broader cultural structures. Her images move fluidly between the intimate and the monumental, from self-portraits and family scenes to vast civic gatherings. Throughout, her practice is driven by an insistence on care, both for her subjects and for the communities they inhabit. Opie’s work does not seek spectacle but builds meaning through precision, restraint and sustained attention. This commitment has positioned her as a central figure in contemporary portraiture.

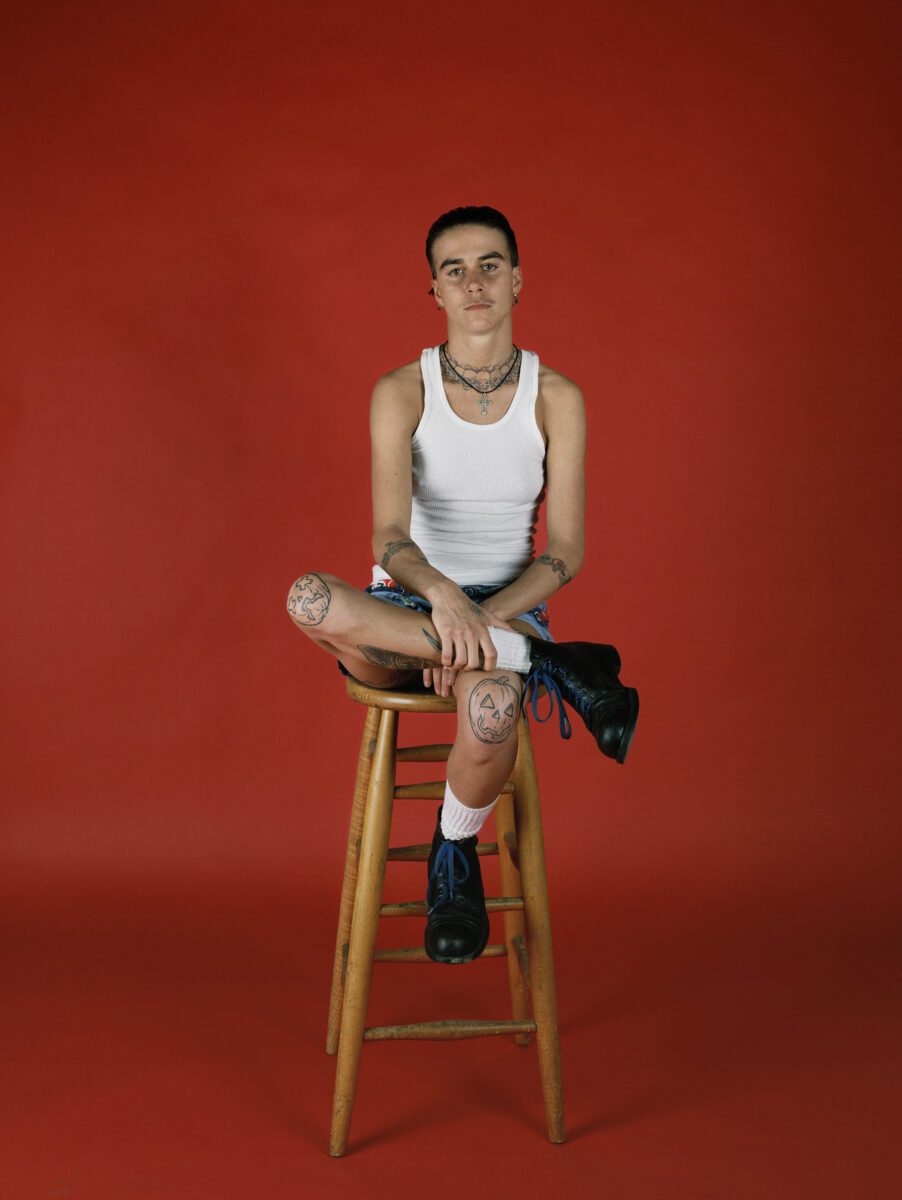

Emerging in the early 1990s, Opie gained recognition for portraits that challenged dominant narratives around gender, sexuality and power. Her seminal series Being and Having from 1991 comprised of 13 portraits of Opie as ‘Bo’ and her leather dyke community enacting their moustachioed masculine alter – egos. Against flat, brightly coloured backdrops, subjects meet the camera with self-possession, adorned with moustaches and leather caps that complicate ideas of masculinity. These portraits reframed queer identity not as marginal but as sovereign, borrowing from art history to rewrite its exclusions. Opie’s work demonstrated from the outset that representation is inseparable from politics. The series remains a touchstone for understanding her commitment to radical and unapologetic visibility.

This spring, the National Portrait Gallery stages the first major museum exhibition of Catherine Opie’s work in the UK. Titled Catherine Opie: To Be Seen, the exhibition brings together more than 80 photographs spanning 30 years of her career. Created in close collaboration with the artist, it also includes a series of interventions within the Gallery’s permanent collection. The exhibition marks a significant moment for British audiences, offering a comprehensive view of a practice that has shaped global photographic discourse. It arrives at a time when questions of identity, visibility and representation are increasingly central to institutional practices. The Gallery becomes an active participant in Opie’s enquiry.

The significance of this exhibition lies in its placement within a national museum devoted to portraiture. Opie’s work asks pointed questions about who is celebrated within such institutions and how histories are constructed through images. By situating her photographs alongside historic portraits, the exhibition exposes the values that underpin traditional canons. It invites viewers to consider how national identity is shaped by inclusion and omission alike. In this context, her work resonates with that of Zanele Muholi, whose portraits of Black LGBTQIA+ communities insist on visibility as a form of self-determination. Both artists use formal clarity and deliberate composition to assert agency and counter histories of erasure.

Designed by architect Katy Barkan, the exhibition unfolds across three interconnected rooms that engage directly with the surrounding galleries. The first room, conceived as a perfect square, presents Opie’s earliest exhibited portraits, including Being and Having. Here, self-portraits sit alongside images of friends and collaborators, collapsing the distance between artist and subject. The second space deliberately collides with an existing Gallery wall, presenting portraits and landscapes shaped by Opie’s engagement with art history. Baroque lighting and compositional gravity recall painting while remaining resolutely photographic. The final room gathers figures from series such as High School Football and Surfers, exploring masculinity and communal identity through spatial compression.

Across these spaces, Opie’s refusal of sensationalism becomes a defining feature. Grounded in the documentary tradition, her work favours nuance over shock and duration over immediacy. Her portraits of LGBTQ+ communities, artists, children and political crowds are attentive rather than declarative. As Clare Freestone, Curator of Photography at the National Portfrait Gallery, observes, Opie’s approach is rooted in “a deep sense of care for her community”. That care is evident in the way subjects are afforded time, agency and complexity. The images resist easy interpretation, instead encouraging sustained engagement.

Opie’s broader practice extends far beyond studio portraiture, encompassing landscapes, architecture and civic life. Projects documenting Los Angeles freeway systems, Catholic churches and American political events reveal her interest in the structures that shape collective experience. Photographs from Barack Obama’s inauguration sit alongside images of Tea Party rallies and LGBTQ+ rights protests. These works collapse distinctions between private belief and public performance. They also underscore Opie’s understanding of portraiture as something that can be collective as well as individual.

Her work resonates with a new generation of photographers exploring visibility and social identity. Tyler Mitchell, celebrated for his vibrant portraits of Black youth, foregrounds optimism and selfhood while challenging the historic absence of Black bodies in major cultural institutions. LaToya Ruby Frazier’s intimate documentation of family and community life interrogates structural inequities in ways that echo Opie’s attention to social context and care. Together with Zanele Muholi, these artists form a lineage of portraiture invested in both political accountability and aesthetic precision. Their approaches underscore portraiture’s capacity to insist on recognition without reducing the subject to stereotype. In dialogue with Opie, their work illuminates the evolving possibilities of seeing and being seen.

At the core of Opie’s practice is a belief in the transformative potential of visibility. Her portraits assert that being seen is not a passive act but a form of civic participation. This ethos is articulated by the artist herself, who hopes audiences will leave with “a broader understanding of what portraiture can achieve – that in our culture of creating portraits of known nobility and a kind of celebrity, that everyone begins to understand identity through being seen”. In a culture preoccupied with celebrity and spectacle, Opie redirects attention to everyday lives and overlooked communities. Her work insists that identity is shaped through mutual recognition. Portraiture becomes a shared space rather than a hierarchy.

Catherine Opie: To Be Seen draws these concerns back to the institution itself. Through interventions across seven collection galleries, the exhibition questions how the National Portrait Gallery has historically defined significance. It asks whose faces have been preserved and whose have been omitted. Opie creates new narratives that sit alongside established histories. The result is a productive tension rather than a rupture. Viewers are encouraged to reflect on how institutions evolve and whom they serve.

The exhibition charts a career defined by intellectual exactitude, formal precision and profound empathy. More importantly, it proposes a vision of portraiture as an active, responsive practice, attentive to social and political conditions. In bringing these works to the UK for the first time at this scale, the National Portrait Gallery affirms the continued relevance of the genre. Opie’s photographs remind viewers that to be seen is to be acknowledged as part of a shared cultural fabric. They demand care, attention and reflection, demonstrating the enduring power of portraiture to shape the way society understands itself. Her work exemplifies how the personal and political can coexist within a single frame.

Catherine Opie: To Be Seen is at National Portrait Gallery, London 5 March – 31 May: npg.org

Words: Shirley Stevenson

Image Credits:

1&6. Pig Pen, 1993 © Catherine Opie, courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles; Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, London, and Seoul; Thomas Dane Gallery.

2. Alistair Fate, 1994 © Catherine Opie, courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles; Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, London, and Seoul; Thomas Dane Gallery.

3. Flipper, Tanya, Chloe & Harriet, San Francisco, California, 1995 © Catherine Opie, courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles; Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, London, and Seoul; Thomas Dane Gallery.

4. Abdul, 2008 © Catherine Opie, courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles; Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, London, and Seoul; Thomas Dane Gallery.

5. Daniela, 2009 © Catherine Opie, courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles; Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, London, and Seoul; Thomas Dane Gallery.