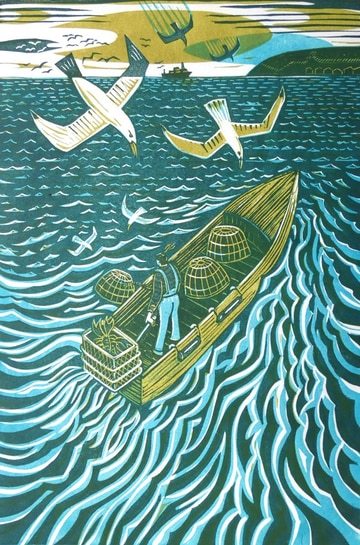

Kit Boyd was recently commissioned by Penguin Publications to do what he does best: create four linocuts to accompany the latest historical novel by Dr James Fox, Craftland. The book takes readers on a journey from the Isles of Scilly to the Scottish Highlands, seeking out Britain’s last great craftspeople. An homage to the nation’s lost arts and vanishing trades, the novel celebrates the extraordinary men and women who continue to practise traditional artisan skills. Boyd depicted a rush weaver on the River Great Ouse, the two last coopers in Northern Ireland, and a coppice worker deep in a Chilterns forest. He also created a portrait of Sarah Ready, pictured below, “a remarkable fisherwoman,” Dr Fox declares, “who has played a central role in reviving the critically endangered craft of withy-pot making.”

Dr Fox has described Boyd’s work as “a small miracle of rhythm and pattern” — a sentiment with which I concur, and one that guides much of our discussion at the artist’s Thameside studio in North Greenwich. Here, I am met by a treasure trove of prints hung, framed, boxed and piled high in various corners of his workshop. Miscellaneous trinkets, stashes of collected materials and a library of books envelop the four walls, punctuated by two desks, a filing cabinet and, lastly, Boyd’s noble steed: the etching press. The workshop feels much like a Boydian landscape: abundant, everything in its rightful place and brimming with life.

Boyd is known for his linocuts and monoprints, which explore our relationship with landscape and our place within nature. He follows in the footsteps of Samuel Palmer and identifies closely with Neo-Romantic figures such as Paul Nash, Graham Sutherland and John Craxton. Where the post-war Romantics sought refuge from the horrors of conflict, Boyd’s images offer respite from a frantic contemporary world, in which media, technology and modern, inorganic infrastructure conspire against quietude and contemplation.

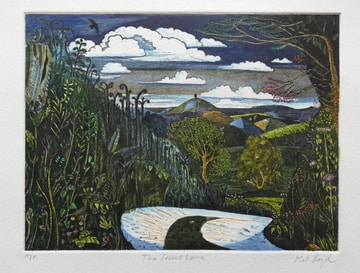

While his work is firmly grounded in the Romantic tradition, Boyd reinvents it through his own quasi-Surrealist sensibility. “These aren’t just representations of landscape; I am capturing the spirit of a place,” he explains. His bucolic scenes, visual feasts for those inclined towards pareidolia, feel distinctly alive: a river becomes the head of a crow, a tree assumes a watchful presence, and a bird tilts into something ominous and otherworldly.

Within this animate space, Boyd often introduces a small human figure, walking into the distance or lingering just out of reach, quietly drawing the viewer into these strange yet familiar lands. The effect is subtle yet immersive, as if we have stepped into the composition itself, accompanied by a presence that is both natural and sentient. Boyd does not merely depict nature; he restores our intimacy with it. The result, however, is not one of simple calm or passive admiration. In his world, nature is charming and unnerving in equal measure, and we, as guests within it, would do well to respect its power.

I ask Boyd whether he believes there is something that Samuel Palmer saw in the British landscape that today’s viewers struggle to connect with. He agrees that an undeniable disconnection from the natural world exists, exacerbated by city living and the spread of modern infrastructure. Although his work does not begin from an overtly political standpoint, an environmental commentary is unmistakably present. He speaks firmly of the role that art can play in conservation and land protection, again citing Palmer as an example. Despite the proximity of major roads, the Darent Valley landscape that inspired Palmer was saved from a proposed motorway development in the late twentieth century. Today, the circular walking route around Shoreham, Kent, guides visitors through the “Valley of Vision” immortalised in Palmer’s paintings. For Boyd, this stands as a powerful reminder of art’s ability not only to reflect the world, but to change it.

Our conversation turns, inevitably, to the rise of artificial intelligence. We discuss the unchecked spread of social media and the fear of consuming content, real or fake, until we become numb to what the world truly has to offer. I ask Boyd if he thinks that we are losing our ability to experience wonder. He pauses before offering a thoughtful, ambiguous nod. Boyd believes that, although something has been lost, a shift is beginning to take place. “People are searching for authenticity, and for a slower, more meaningful form of escapism. They’re going offline.” Perhaps this is why collectors are so instinctively drawn to his work. Boyd’s landscapes remind us that there is still magic in the world. They are, as Dr Fox so perfectly puts it, small miracles of rhythm and pattern.

Boyd’s work possesses a rare capacity to truly stimulate the imagination, populated as it is by a cast of expansive sheep fields, mysterious birds, ancient roaming lanes and rising moons. The narratorial quality that permeates his portfolio leaves it open to interpretation, a quality further heightened by his shifting colour palette.

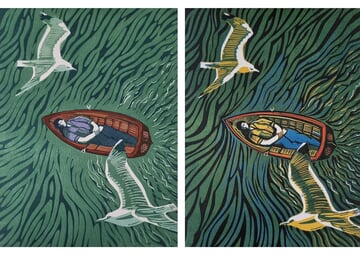

Boyd enjoys hand-colouring his etchings and producing linocuts in variable editions, allowing subtle changes in hue and tone to transform atmosphere and mood. When the gradient is adjusted even slightly, a single scene can tell an entirely different story. In Phases of the Moon, small windswept leaves and nodding, tear-shaped petals burst forth in an animated spectacle of seasonal foliage. The colours are pure and bold, yet retain a certain woolliness that feels organic and intimate, the way I imagine the fine hairs lining flower stems might feel.

“It’s about death!” one critic declared when viewing The Dreamer (2021), pictured above, while others discerned themes of loneliness and meditation. It is a remarkable feat that one image can elicit such divergent readings, particularly when the subject matter appears so firmly rooted in the recognisable world. His visual language carries enough realism to feel familiar, even nostalgic, while retaining a peculiarity that invites, without a doubt, wonder.

Rise Art would like to thank Dr. James Fox, author of Craftland (2025), for contributing the following text on Kit Boyd’s work:

I have admired Kit Boyd’s work for more than a decade. His quietly romantic landscapes recall the very best British art, reminding me of my heroes Samuel Palmer and Paul Nash. Boyd’s prints and paintings transport us into a world that shimmers with magic, where every curving path or twisting branch seems charged with sentience.

Earlier this year, Kit made four wonderfully lyrical linocuts for my new book, Craftland, which explores Britain’s lost and endangered crafts. He depicted a rush weaver on the River Great Ouse, the two last coopers in Northern Ireland, and a coppice worker deep in a Chilterns forest.

This image is a portrait of Sarah Ready, a remarkable Devon fisherwoman who has played a central role in reviving the critically endangered craft of withy-pot making. She weaves her own crab and lobster pots, as part of a broader effort to model a more sustainable way of fishing. Kit’s artwork is a small miracle of rhythm and pattern.