As Lebanon grapples with the consequences of the war between Israel and Hezbollah, which has already claimed the lives of more than 2,500 Lebanese and 60 Israelis, the country’s vibrant art scene, long a bastion of creativity in the region, has not been spared.

According to the Lebanese publication Agenda Culturel, Lebanon is home to around 92 art galleries, 103 museums, and 102 cultural spaces. While many institutions have closed, others remain open with reduced hours, determined to provide a respite from the surrounding destruction.

Hezbollah and Israel have traded fire consistently in the year since the war began in nearby Gaza. But on 17 September, the conflict escalated dramatically when Israel detonated thousands of pagers belonging to Hezbollah members in Lebanon, followed by the assassination of the group’s leader, Hassan Nasrallah. Since then, Israel has intensified air strikes in Lebanon and areas it considers Hezbollah strongholds, including the ancient city of Baalbek and the Dahieh neighbourhood in southern Beirut. The attacks have displaced more than 1.2 million people, many of whom have sought refuge in Beirut. Hezbollah, meanwhile, increased its rocket and drone attacks on northern cities in Israel and military sites; the flighting is believed to have displaced around 60,000 Israelis.

Against this backdrop, Saleh Barakat Gallery in Beirut has decided to remain open but with limited hours, prioritising safety as many people avoid venturing far from home. “We are trying to figure out how to keep the artistic and cultural framework alive,” Saleh Barakat, the gallery’s founder, tells The Art Newspaper.

Although Barakat has cancelled an exhibition by Dia Azzawi, an Iraqi artist often described as a pioneer of Modern Arab art, he is preparing a new show featuring local artists instead. “There are a lot of people in Beirut and those people need to breathe. Art spaces allow people to get out of politics, to escape,” he says. Barakat also spends his time with artists, advising them to focus on their work to keep them away from the “dark news” on television.

It’s better to be here because we need to defend our presence, our interests, our lives

Saleh Barakat, gallerist

Recent events have led Barakat to send his children abroad and he has helped some of his staff relocate from some of the more dangerous suburbs. Looking ahead, Barakat hopes to connect with international clients at the forthcoming art fair Abu Dhabi Art (20-24 November). “I’m heavily invested. I have spent a lot of money [on the fair], but if it’s not going to happen, it won’t,” Barakat says. “If I cannot go, I think it’s better to be here because we need to also defend our presence, our interests and our lives,” he adds.

Nabil Nahas’s exhibition at Saleh Barakat Gallery Image: courtesy of Saleh Barakat Gallery

Galerie Tanit is taking a similar approach, remaining open for limited hours or by appointment. Naila Kettaneh Kunigk, the founder of the gallery, says that an exhibition on Bettina Khoury Badr, which opened on 29 August and was due to run until 3 October, was cut short. “We are all terribly impacted,” Kunigk says.

She hopes the gallery’s participation in events this month such as Paris Photo (7-10 November) and Abu Dhabi Art can offer some financial relief. But reduced flights from Beirut and higher shipping costs have added to the gallery’s challenges. She suggests the international art community could support the struggling Lebanese art scene by offering discounted spaces at events and by supporting Lebanese artists.

Many galleries and art institutions in Beirut have closed their doors entirely. “We are extremely worried and shaken by what is going on,” says Joumana Asseily, the founder of Marfa’ gallery. While the gallery is closed indefinitely, the staff are trying to operate remotely and attend international art events, including last month’s edition of the Frieze London art fair where Marfa’ had a stand. “We try as much as we can to persevere in our work and support our artists despite these terrible times,” Asseily says.

A vibrant city silenced

The conflict has also impacted universities. The fine arts department of the American University of Beirut (AUB), which has two galleries in the capital, has moved its courses online and cancelled its forthcoming exhibitions. “Beirut is a very noisy and vibrant place but very quiet when there is any kind of tension. Right now, it is very quiet, even electronically,” says Octavion Esanu, the director and curator of AUB galleries, speaking from Tokyo.

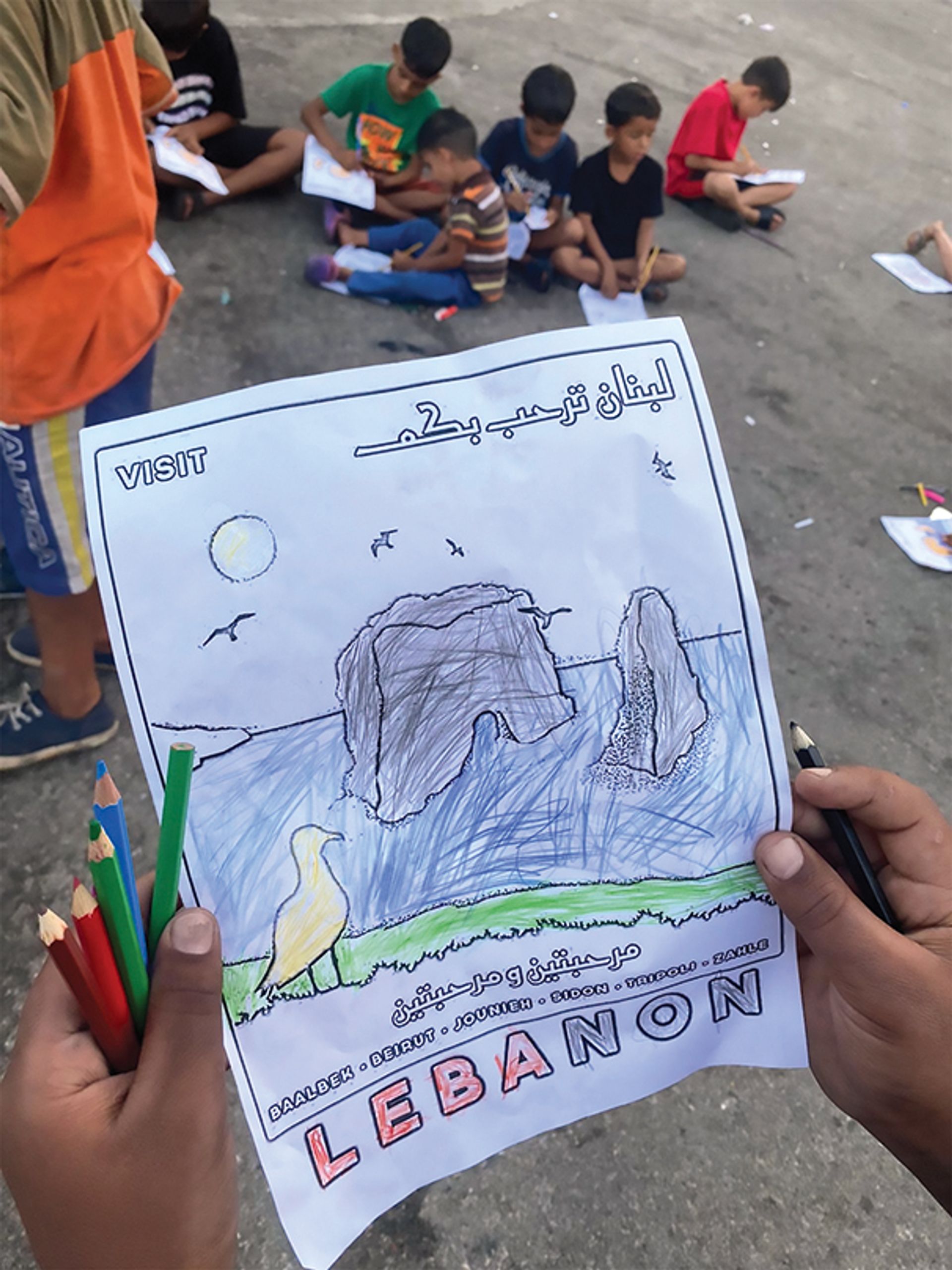

A project in Beirut run by art students and volunteers helps displaced children deal with trauma through art Photo: Ahmad Mofeed

Esanu divides his time between Lebanon and Japan. He mentions that one of AUB’s galleries has been assessed as a potential shelter for displaced people and that art students are using their skills to support relocated children through art initiatives.

“As adults, we offer workshops for children who are just like us. We are all living through war—some of us are displaced, or our families are,” says Ahmad Mofeed, an art student at AUB and one of the organisers of the initiative. “We are art students or volunteers, and we have nothing but art to document what we’re experiencing,” Mofeed adds.

The workshops, largely held in schools that have now been closed, serve around 50 children with the help of 17 volunteers. They focus on three techniques: group drawing, portraiture drawing and group singing. Mofeed says these activities encourage collective creativity, deep self-reflection, and the expression of emotions through art, while also fostering a sense of Arab national identity and belonging.

Other artists are stepping in to help by raising funds. Abed Al Kadiri, a Paris-based multidisciplinary Lebanese artist, is working on the third edition of his project Today, I Would Like to Be a Tree in collaboration with the Katara Art Centre in Doha. The project involves creating murals on panels, which are then sold, with all proceeds going to a relief fund for displaced Lebanese people. The first two editions, held in 2020 and 2023, raised funds for the victims of the Beirut port explosion and for Palestinian children, respectively.

“We have more sensitivity towards humanity in general than politicians. If art can be a form of resistance and support, it should really take that form of support—to really try to gather funds or to help people in these circumstances,” Kadiri says, speaking from Amman, Jordan, where he has relocated with his family.

Kadiri, who was born in 1984, knows war all too well. He lived through Israel’s 18-year occupation of southern Lebanon that ended in 2000, and the previous war between Israel and Hezbollah in 2006. He spent his early years in shelters across numerous cities.

The violence he witnessed remains a central theme in his work. Determined to shield his son from the same horrors, he flew to Lebanon and relocated his family to a village in the mountains. But the respite was short lived. After an explosion near their building, he decided to evacuate his family from Lebanon on 4 October.

“I believe that this is really inhuman and a really traumatising experience, and I don’t want my son to witness such things,” he says.

Others, have been unable to work amid the violence. The artist Maysam Hindy was living on the border of Beirut’s Dahieh neighbourhood when the air strikes began. The nightly bombings by Israel in nearby areas became so terrifying that her family eventually fled to a relative’s house outside the city.

Hindy’s first solo exhibition at Marfa’ gallery took place in May 2023, months before the war in Gaza broke out. She then spent the next ten months in her studio making art.

“I told myself, let’s archive to survive because death is very near,” she says. The first painting in her series was titled A Place Where We Could Hide, a reflection on her constant anxiety about war, bombs and death. Hindy explains that she anticipated the escalation of the conflict in Lebanon. For now, her camera has become her new medium, not just for art, but for“archiving family moments and the displacement we’ve been through”.

‘Mentally, I’m feeling every bomb’

Even those who are not close to the explosions are still deeply impacted by the recent conflict. Anachar Basbous, a leading sculptor, lives in a village in the mountains around 50km from Beirut. While the sounds of drones and fighter jets are frequent, the bombings are distant. “I’m physically far, but mentally I’m feeling every bomb hitting Beirut or the south. It’s impossible to be far and truly at peace, even if it is calm here in my village,” Anachar says.

Immersed in his work, he says that, for the first time in his career, his art is directly shaped by his emotions, an “accumulation of division and destruction”. This has led him to make works using concrete blocks, which he says is the “form that I see in every image of destruction in the Middle East”.

“Times are tough and we have to do what we do best. For me, it’s creation, it’s art—saying we are here and this is the way we are expressing ourselves,” Anachar says.

The artist hopes that art institutions will step in to support Lebanese artists by providing them with the space to present their work. “It would be a very nice idea to help us, because it’s suffocating here,” he says. For now, Anachar’s exhibitions in Lebanon are on hold but his sculptures are due to be presented by Saleh Barakat Gallery at Abu Dhabi Art this month.

The renowned Lebanese writer and painter Afaf Zurayk, whose work is in the British Museum’s collection, has been unable to paint since the war began. Living in the mountains, she is currently writing, “in the hope of eventually painting the texts and turning them into another painted word piece expressing and recording life in these troubled times”.

Instead of an interview, Zurayk shared several of her recent poems with The Art Newspaper, which document the ongoing events, including this one:

Terrains of hate challenge my faith, my certainty. Fighting fear, my thoughts become words, some comfort, but most elude, me.

I begin to see in multiples—layers, thoughts, realities.

I utter “please forgive”, we are less than what we can be.

War does not require courage, the courage to have a soul.

Our bodies die forgiving our souls, regretting.

I pray for those of us remaining.