The Van Gogh Museum is abandoning its 50-year policy of generally avoiding discussions of fakes. As the main research centre on Van Gogh’s work, the Amsterdam museum has made a welcome decision to be more open about publishing scholarly material in this controversial field.

Breaking its silence, the museum identifies three “Van Goghs” in private collections which are not the real thing. They include a painting of a peasant woman which was previously authenticated by the museum and then sold as recently as 2011 by Christie’s. Having gone for nearly $1m, it is now dismissed as a fake.

This research is published in the October issue of The Burlington Magazine, in an article by a trio of Van Gogh Museum specialists—Teio Meedendorp, Louis van Tilborgh and Saskia van Oudheusden. They downgrade works that were accepted as authentic in the definitive 1970 catalogue raisonée by Jacob-Baart de la Faille.

AUTHENTIC: Van Gogh’s Interior of the Grand Bouillon-Restaurant le Chalet, Paris (November-December 1887), private collection

FAKE: Interior of a Restaurant (mid 20th century), private collection

Photograph: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

For decades Interior of a Restaurant was regarded as a second version of an authentic painting, Interior of the Grand Bouillon-Restaurant le Chalet, Paris (private collection, November-December 1887). This was understandable, since Van Gogh would sometimes make another version of a composition, either for a gift or to achieve a slightly different artistic effect.

The second version of the restaurant scene, which only surfaced in the 1950s, was recently studied after its owner submitted it for possible authentication. Museum specialists decided that the “broad, rough and sketchy brushwork” did not resemble the style of the original and the colours did not match Van Gogh’s palette of his Paris period. The colours also included Manganese blue, a synthetic pigment only patented in 1935.

In the original painting the red flowers can be identified as autumn begonias, which presumably graced the restaurant tables in November or early December 1887, when the picture was completed. The artist of the second version was working from an early black-and-white photograph and interpreted them as yellow sunflowers, which would have been over by the end of September.

As the three authors of the Burlington article point out, “the addition of the sunflowers strongly suggests that this is not just an innocent, clumsy copy, but a deliberate forgery”.

Whoever added the sunflowers had obviously associated them with Van Gogh—and their presence on the restaurant tables must have made the picture superficially more attractive to potential buyers. When the copy was made, in the 1950s, it was wrongly thought that the original dated from the summer of 1888, but much later research showed that it was done in the very late autumn of 1887.

AUTHENTIC (left): Van Gogh’s Head of a Woman with a green Bonnet (late 1884-early 1885), private collection

FAKE (right): Head of a Woman (1902-09), private collection

Photographs: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

The second case cited in the Burlington article is Head of a Woman, which came from the estate of Gerbrand Visser, a controversial part-time art dealer who died in 2007. The following year the painting was authenticated by the Van Gogh Museum and accepted as the picture recorded in the de la Faille catalogue.

In 2011 the painting, the Visser painting, then entitled Head of a Peasant Woman with dark Cap, was offered at Christie’s New York with the museum’s authentication. It sold for $993,250. What happened next is a salutary reminder that attributions can change when new information emerges.

In 2019 the specialists at the Van Gogh Museum got a surprise when they were asked to authenticate another remarkably similar painting of a Nuenen peasant woman, submitted by a French owner. This posed a puzzle. Was this newly emerged picture a second version by Van Gogh’s own hand or a copy made by someone else? Or was there a problem with the Christie’s peasant woman?

After technical research (which included an examination of the canvas, the white ground beneath the artist’s paint and the application of the paint), it became clear that the Christie’s painting had been “executed by a copyist who almost certainly worked from the original and did his or her utmost to replicate Van Gogh’s painting as accurately as possible“.

When was the copy made? The original belonged to Vincent’s mother until 1902 and in 1909 it disappeared into an inaccessible private collection. It is therefore likely that the copy was made in 1902-09, although it only appeared around a hundred years later. The museum specialists concluded that it is “unclear” whether the copy had been done with the intention of passing it off as an autograph Van Gogh.

A Christie’s spokesperson told us this week: “We take every measure to ensure the authentication of all works consigned for sale, including seeking the expertise by the most eminent experts around the world. The work was authenticated in 2011, having been confirmed as a Van Gogh. As a matter of practice, we cannot comment any further on individual consignments.”

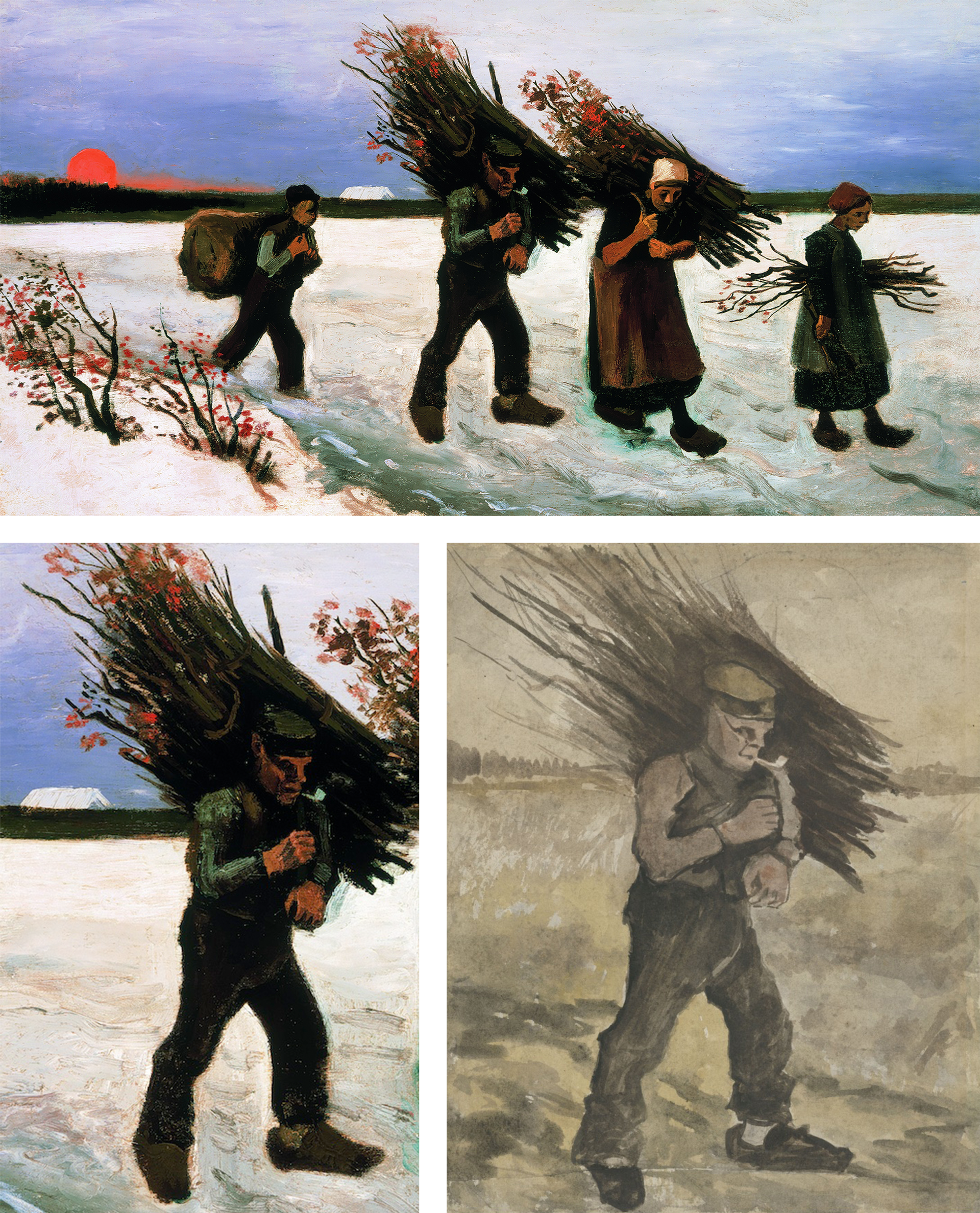

AUTHENTIC (above): Van Gogh’s oil painting, Wood Gatherers in the Snow (August-September 1884), private collection

AUTHENTIC (below left): Van Gogh’s Wood Gatherers in the Snow (detail)

FAKE (below right): Watercolour of Wood Gatherer (1904-12), private collection

Photograph (below right), Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

The third example cited in the Burlington article is a watercolour of a Nuenen man who appears in the oil painting Wood Gatherers in the Snow (August-September 1884). The watercolour, which first surfaced in 1912, was later accepted in de la Faille catalogue. This recorded that it had been sold at Sotheby’s in 1957 and bought by British businessman the Earl of Inchcape (Kenneth Mackay).

When the watercolour of the Wood Gatherer was shown to the Van Gogh Museum in 2020 it was rejected. The specialists concluded that the artist had worked from a photograph of the full painting, which was first published in 1904. The copy must therefore have been made in 1904-12.

Among the damning evidence is that the copyist had failed to spot the lengthy vertically-held stick that Brabant peasants would use to help carry bundles of wood on their backs, a feature which is difficult to spot in early photographs of the original painting. These black-and-white photographs also do not clearly show the snow-covered roof of the farmhouse in the background (behind the man), so this detail was missed by the copyist.

Interestingly, two of the three fakes cited in the Burlington were both done in the very early years of the 1900s, a decade or two after Van Gogh’s death. During the artist’s lifetime he failed to sell his work, yet it soon became valuable enough to paint a copy in homage—or to forge for profit.

Other Van Gogh news

- On 27 September three Just Stop Oil protestors threw tomato soup at two of the Sunflower paintings in the National Gallery’s exhibition Van Gogh: Poets & Lovers (until 19 January 2025). The pictures (National Gallery, London, 1888 and Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1889) are both glazed, so there was no damage to the artworks, although the frames may have suffered (the London frame is 17th century and the Philadelphia one is new). The attack occurred at 2.30pm and the gallery was immediately closed, to allow conservators to remove the pictures from the glass and frames. The exhibition reopened with the Sunflowers at 5.45pm. This latest attack follows an earlier one on the National Gallery’s Sunflowers on 14 October 2022. The three protesters involved in this latest incident (Stephen Simpson, 71 and Mary Somerville, 77, both from Bradford, and Philippa Green, 24, from Penryn) were arrested and have pleaded not guilty to criminal damage. They are due to appear at Southwark Crown Court on 28 October.

The National Gallery’s Sunflowers on a yellow background (left) and the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s Sunflowers on a turquoise background (right), photographed this week after the protest attack

The Art Newspaper, London

• Bonhams auction house in London is selling an important Dutch drawing by Van Gogh, Sien’s Mother’s House seen from the Back Yard (May 1882). Owned by a private collector in Asia, it will be offered on 10 October, with an estimate of £800,000-£1.2m. We earlier revealed that Sien Hoornik, who was Van Gogh’s lover in The Hague, died by suicide in Rotterdam in 1904.

Van Gogh, Sien’s Mother’s House seen from the Back Yard (May 1882)

Bonhams, London